Table of Contents

- [What Does a Railroad Engineer Do?](#what-does-a-railroad-engineer-do)

- [Average Railroad Engineer Salary: A Deep Dive](#average-railroad-engineer-salary-a-deep-dive)

- [Key Factors That Influence Salary](#key-factors-that-influence-salary)

- [Job Outlook and Career Growth](#job-outlook-and-career-growth)

- [How to Get Started in This Career](#how-to-get-started-in-this-career)

- [Conclusion](#conclusion)

There are few careers that capture the raw power and enduring importance of the American landscape quite like that of a railroad engineer. It's a profession woven into the very fabric of the nation's commerce and history, a role that commands respect, requires immense responsibility, and offers a unique view of the world from the controls of a multi-ton locomotive. If you've ever felt a thrill at the sound of a train horn echoing through a valley or wondered about the life of those who guide these steel giants, you've come to the right place. This isn't just a job; it's a calling with significant financial rewards.

For those with the right blend of focus, technical aptitude, and resilience, a career as a railroad engineer offers a highly competitive salary, often reaching well into the six figures. The median pay for this profession sits comfortably around $73,990 per year, but with experience and overtime, it's not uncommon for seasoned engineers to earn over $120,000 annually. I once spoke with a veteran engineer who described his job not just by the miles he traveled, but by the tangible impact he had. "Every car I pull," he said, "is food for a family, a car for a new driver, or the materials for a new home. You feel the weight of that responsibility, and the pay reflects it."

This guide is designed to be your definitive resource, a comprehensive map to navigate the world of a railroad engineer. We will delve deep into the salary you can expect, the factors that shape your earnings, the day-to-day realities of the job, and the precise steps you need to take to climb aboard this rewarding career. Whether you're a recent high school graduate exploring options or a seasoned professional considering a change, this article will provide the expert insights and data-backed answers you need.

---

What Does a Railroad Engineer Do?

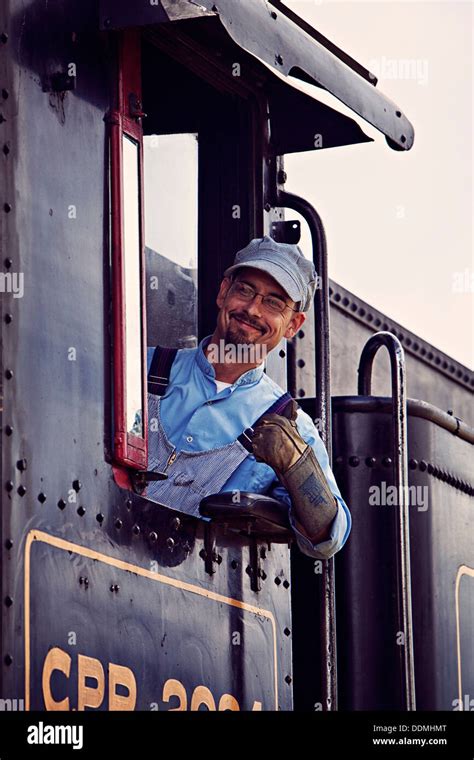

The title "Railroad Engineer" might conjure images of someone designing bridges or track layouts, but in the context of railroad operations, the engineer is the highly skilled professional in the driver's seat of the locomotive. Officially known as Locomotive Engineers by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), they are the pilots of the railway, responsible for the safe, efficient, and timely operation of freight and passenger trains.

Their role is a complex blend of technical skill, intense concentration, and strict adherence to a vast set of safety protocols. They work in tandem with a Railroad Conductor, who is responsible for the train's cargo and crew. While the conductor manages the train's overall activities, the engineer's domain is the locomotive itself—interpreting signals, controlling speed, and managing the immense mechanical forces at play.

Core Responsibilities and Daily Tasks:

The duties of a railroad engineer are far more extensive than simply moving a throttle forward. They are meticulously structured around safety and precision.

- Pre-Departure Inspections: Before any journey, engineers perform rigorous checks on the locomotive. This includes inspecting engines, fuel levels, brakes, sanders (for traction), and all control systems to ensure they are functioning according to federal regulations.

- Interpreting Orders and Signals: They receive "train orders" or "track warrants" from the dispatcher, which detail the route, speed limits, and any specific instructions or hazards along the way. While in motion, they must constantly monitor and interpret trackside signals, radio communications, and onboard computer displays, such as the Positive Train Control (PTC) system.

- Operating the Locomotive: This is the core function. Engineers use throttles to control speed, air brakes to slow and stop the train, and dynamic brakes to use the momentum of the train's motors to slow down on grades. They must master the art of handling the train's "slack"—the movement between coupled cars—to prevent derailments or damage to cargo.

- Monitoring and Troubleshooting: Throughout the trip, they monitor gauges, meters, and computer systems for any signs of mechanical or electrical issues. They need a strong mechanical aptitude to diagnose problems and, if possible, perform minor running repairs.

- Communication: Constant and clear communication with the conductor, dispatchers, and other train crews via a two-way radio is paramount for safety and coordination.

- Compliance and Reporting: Engineers are responsible for complying with all company rules and Federal Railroad Administration (FRA) regulations. They must also complete detailed reports on delays, equipment malfunctions, and any incidents that occur during their shift.

### A Day in the Life: The Freight Haul

To make this tangible, let's follow a fictional road engineer named Sarah on a typical run:

- 2:00 AM: The phone rings. It's the crew caller. Sarah has been called for a 4:00 AM assignment—an eastbound freight train heading 250 miles to the next major yard. She has two hours to get ready and report for duty.

- 3:45 AM: Sarah arrives at the yard office, signs in, and meets her conductor, Mike. They review their track warrants, weather conditions, and any special bulletins about the track ahead.

- 4:15 AM: They head to their locomotive. For the next 30 minutes, Sarah meticulously inspects the three engines leading their 8,000-foot-long train. She checks the fuel, oil, and water, tests the brakes, and verifies that the PTC system is online and synced with dispatch.

- 5:00 AM: With a clear signal from the yardmaster and confirmation from Mike that the train is ready, Sarah gets clearance from the dispatcher. She eases the throttle forward, skillfully managing the slack action down the long string of cars, and the train begins its journey.

- 5:00 AM - 1:00 PM: The next eight hours demand unwavering focus. Sarah navigates the mainline, adjusting speed for curves and grades. She communicates with passing trains, calls out signals to Mike for verification, and monitors the onboard systems. They pass through small towns as the sun rises, a moving artery of commerce. A "slow order" comes over the radio, requiring them to reduce speed over a section of track where maintenance is being performed.

- 1:15 PM: They arrive at the destination yard. Sarah carefully brings the massive train to a halt at the designated siding. Her operational duties are complete.

- 1:45 PM: After completing post-trip inspections and filing their final paperwork, Sarah and Mike are "released from duty." Because they are more than a day's travel from their home terminal, the railroad puts them up in a hotel to rest before their next assignment back home, which could come in the next 10 to 24 hours.

This example highlights the non-traditional lifestyle and immense responsibility that define the role, forming the foundation for the high salary potential it offers.

---

Average Railroad Engineer Salary: A Deep Dive

The salary of a railroad engineer is one of the most compelling aspects of the career, offering a path to a solid upper-middle-class income without the requirement of a four-year college degree. Compensation is robust, driven by the immense responsibility, high level of skill required, and the often demanding, on-call nature of the work. Union representation, particularly with major Class I railroads, plays a significant role in establishing strong wage floors and benefits packages.

It's important to understand that railroad pay is often complex. While some engineers have set hourly rates (especially in yard service), many "road" engineers are paid based on a combination of mileage and hours worked. This means that longer, faster runs can be more lucrative. Overtime is also a substantial component of total earnings, as federal hours-of-service regulations allow for long shifts.

National Salary Benchmarks

To provide a clear and authoritative picture, let's look at data from several reputable sources.

- The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS): As of its May 2023 Occupational Outlook Handbook data, the BLS reports the median annual wage for locomotive engineers was $73,990. This means half of all engineers earned more than this, and half earned less. The BLS also provides a salary spectrum:

- Lowest 10% earned less than $58,320

- Highest 10% earned more than $107,240

It is critical to note that the BLS figure represents a baseline and often doesn't fully capture the extensive overtime pay that many engineers accrue.

- Salary.com: This aggregator provides a more granular look, often reflecting the higher earning potential with overtime. As of late 2023, Salary.com reports the average Locomotive Engineer salary in the United States is $88,582, with the typical range falling between $74,750 and $104,809. This range likely includes a more typical mix of base pay and additional compensation.

- Glassdoor: Based on user-submitted salary data, Glassdoor reports an estimated total pay for a Railroad Engineer in the U.S. at $101,235 per year, with an average base salary of around $82,311 and additional pay (bonuses, overtime) of nearly $19,000.

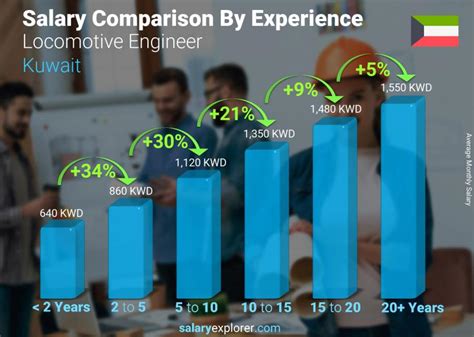

Salary Progression by Experience Level

Like any profession, experience is a primary driver of income growth. A new engineer fresh out of training will earn significantly less than a 20-year veteran who gets first choice of the most desirable and high-paying routes.

Here is a typical salary progression, synthesized from industry data:

| Experience Level | Typical Annual Salary Range (including overtime) | Key Characteristics |

| :--- | :--- | :--- |

| Trainee / Entry-Level (0-2 years) | $60,000 - $85,000 | In training or recently certified. Still learning routes and equipment. Often works on-call with less predictable schedules, including yard work or lower-priority freight lines. |

| Mid-Career (3-10 years) | $85,000 - $115,000 | Fully proficient with multiple locomotive types and routes. Has built seniority, allowing for better schedule and route choices. Consistently works on mainline freight or passenger runs. |

| Senior / Veteran (10+ years) | $110,000 - $140,000+ | Top-tier seniority. Holds the most desirable and often highest-paying assignments (e.g., long-haul "priority" freight). May be involved in training new engineers. Earnings can be significantly higher with overtime. |

*Sources: Synthesized from Payscale, Glassdoor, and data from union agreements.*

Beyond the Paycheck: A Look at Total Compensation

The salary figures alone don't tell the whole story. Railroad companies, especially the major Class I players, offer some of the most comprehensive benefits packages available in any industry.

- Overtime and Mileage Pay: As mentioned, this is the single biggest variable. Federal regulations limit work to 12 consecutive hours, followed by a mandatory 10 hours of uninterrupted rest. This structure leads to significant overtime opportunities. Mileage-based pay systems can further boost earnings for engineers on fast, long-distance routes.

- The Railroad Retirement Board (RRB): This is a critical and unique benefit. Railroad employees do not pay into Social Security. Instead, they contribute to the RRB, a separate federal agency that provides retirement, survivor, unemployment, and sickness benefits. RRB benefits are generally more generous than Social Security, providing a significant long-term financial advantage.

- Health Insurance: Union-negotiated national agreements provide outstanding healthcare benefits, often with very low premiums and deductibles for employees and their families.

- Per Diem Allowances: When engineers are required to rest away from their home terminal ("held away from home"), they receive a tax-free per diem allowance to cover meals and expenses.

- Bonuses and Profit Sharing: While less common than in corporate roles, some railroads offer safety bonuses for achieving injury-free milestones or other performance-based incentives.

- Paid Time Off: Paid vacation and sick leave are standard, with the amount of time off increasing with seniority.

When you combine a base salary that often starts in the $70k range with substantial overtime, exceptional retirement benefits, and top-tier healthcare, the total compensation package for a railroad engineer is formidable and highly attractive.

---

Key Factors That Influence Salary

While the national averages provide a great starting point, an individual railroad engineer's salary is a complex equation determined by a multitude of intersecting factors. Understanding these variables is crucial for anyone looking to maximize their earning potential in this career. This section breaks down the six primary elements that dictate how much you can expect to make behind the controls of a locomotive.

### 1. Years of Experience and Seniority

In the world of railroading, experience is synonymous with seniority, and seniority is king. It is arguably the single most powerful factor influencing not just your salary, but your entire quality of life as an engineer.

- The Trajectory:

- Trainee: Your journey begins as a conductor trainee. During this period (which can last several months), you are paid a training wage, which is significantly lower than a qualified conductor's or engineer's pay.

- Conductor/Assistant: After certification, you'll work as a conductor, typically for several years. This is where you build foundational experience and begin earning a full wage, often starting around $65,000 - $80,000 with overtime.

- Engineer Trainee: When a position opens and you have sufficient seniority, you can enter the engineer training program. Again, you'll be on a training wage.

- Certified Engineer (Low Seniority): Once certified, you enter the engineer workforce at the bottom of the seniority list. You'll likely be "on the extra board," meaning you're on-call 24/7 to cover shifts for engineers who are on vacation, sick, or otherwise unavailable. The work is inconsistent, but the hourly/mileage pay is high, and overtime is plentiful. Earnings often jump to the $80,000 - $100,000 range, but the schedule can be grueling.

- Mid-to-High Seniority Engineer: After 5, 10, or 15 years, you accumulate enough seniority to "hold a bid job." This means you can bid for and win a specific, regular assignment—be it a particular freight run, a yard job with a set schedule, or a passenger route. These jobs offer predictability and are often the most lucrative. A senior engineer on a priority freight line can consistently earn $120,000 - $150,000 or more.

Seniority dictates your ability to choose your job, your location (terminal), your vacation time, and ultimately, your earning potential.

### 2. Company Type and Size

The type of railroad you work for has a profound impact on your salary and benefits. The industry is generally categorized into three main classes, plus passenger services.

- Class I Railroads: These are the giants of the industry. In North America, this includes companies like BNSF Railway, Union Pacific Railroad, CSX Transportation, Norfolk Southern Railway, Canadian National Railway, and Canadian Pacific Kansas City.

- Salary Impact: Class I railroads consistently offer the highest pay scales and the most comprehensive benefits. Their vast networks mean longer hauls, more mileage-based pay opportunities, and extensive overtime. The wages and work rules are governed by powerful national union contracts, ensuring a high floor for compensation. Expect top-tier earnings here, with the potential to reach the $140,000+ figures mentioned for senior engineers.

- Class II Railroads (Regional): These are smaller than Class I's but still significant operations, often connecting specific regions. Examples include the Florida East Coast Railway or the Iowa Interstate Railroad.

- Salary Impact: Pay is still very competitive but may be slightly lower than at a Class I. The routes are shorter, which might mean less opportunity for high mileage pay, but this can sometimes be offset by more regular schedules and less time spent away from home.

- Class III Railroads (Short Line): These are small, local railroads that often serve a specific industry or connect a few towns to a Class I mainline.

- Salary Impact: Short-line railroads typically offer the lowest salaries of the three classes. The work is often more predictable, with regular hours and no long-distance travel, which is a major lifestyle advantage for some. However, total compensation, including benefits, is generally less than what you would find at a larger carrier. An engineer here might earn in the $60,000 - $85,000 range.

- Passenger Rail: This includes Amtrak (national) and various commuter rail agencies like Metrolink (Southern California), Metra (Chicago), or Long Island Rail Road (New York).

- Salary Impact: Passenger engineer salaries are highly competitive and often rival those at Class I freight companies. The work is very different—focused on passenger comfort, smooth acceleration/deceleration, and strict adherence to schedules. The schedules are often more predictable than freight, with defined routes and layovers. A senior Amtrak engineer or a veteran on a major commuter line can easily earn over $100,000.

### 3. Geographic Location

Where you work in the country matters. Salaries are adjusted based on the cost of living, the concentration of rail traffic, and the presence of major rail hubs and company headquarters.

- High-Paying States and Metropolitan Areas: According to BLS data and salary aggregators, states and cities with major rail terminals, ports, and industrial centers tend to pay more.

- Top States: States like Illinois (the nation's rail hub), Texas, California, Nebraska, and Pennsylvania often show higher average salaries due to the sheer volume of freight traffic and the presence of major yards for companies like Union Pacific (headquartered in Omaha, NE) and BNSF (Fort Worth, TX).

- Top Cities: Metropolitan areas like Chicago, Houston, Los Angeles, Kansas City, and Atlanta are critical nerve centers for the rail network, leading to higher demand and pay for qualified engineers. For example, according to Salary.com, a locomotive engineer in Chicago can expect to earn about 5-7% more than the national average.

- Lower-Paying Areas: Conversely, states with less rail infrastructure or that are primarily served by short-line railroads will naturally have lower average salaries. Rural areas in the Southeast or parts of New England might fall into this category, though "lower" is relative in this high-paying profession.

### 4. Area of Specialization (Work Type)

Within the engineer profession, your specific job assignment—your "specialization"—directly shapes your pay structure and earning potential.

- Road Engineer (Freight): This is the classic long-haul role. Road engineers are typically paid by the mile (e.g., a "basic day" might be 130 miles, with additional pay for every mile over that). This creates a direct incentive for efficiency. These roles involve the most time away from home but also have the highest earning potential due to mileage pay and overtime.

- Yard Engineer: Yard engineers work within the confines of a rail yard, breaking down incoming trains and building new ones for departure. They are typically paid a set hourly rate. Their schedules are more regular (e.g., fixed 8 or 10-hour shifts), and they go home every night. The trade-off is a lower top-end salary compared to a road engineer, as there is no mileage pay and often less overtime. A yard engineer might earn in the $75,000 - $95,000 range.

- Passenger Engineer: As discussed, these engineers operate Amtrak or commuter trains. Their pay is often hourly but can be supplemented by trip rates. Their focus on passenger schedules leads to more predictable work patterns than freight. Salaries are excellent, easily clearing six figures with experience, but may not reach the absolute peak of a top-tier freight engineer running priority routes.

### 5. In-Demand Skills and Certifications

While a college degree is not a factor, certain skills and qualifications are essential and can enhance your value.

- Proficiency with Advanced Technology: Modern locomotives are packed with technology. The most critical system is Positive Train Control (PTC), a federally mandated safety system that can automatically stop a train to prevent certain types of accidents. Expertise in operating, troubleshooting, and working seamlessly with PTC is no longer optional—it's a core competency.

- Mechanical Aptitude: While dedicated mechanics handle major repairs, an engineer with a strong understanding of locomotive mechanics can diagnose issues on the road, potentially preventing a minor problem from becoming a trip-ending failure. This skill is highly valued.

- Knowledge of Regulations: A deep, encyclopedic knowledge of the General Code of Operating Rules (GCOR) and specific Federal Railroad Administration (FRA) regulations is paramount. An engineer with an impeccable safety record and a reputation for knowing the rulebook inside and out is an invaluable asset to the company.

- Certifications: The primary certification is the FRA Locomotive Engineer Certification, which is required to operate a train. This certification must be renewed every three years. While there aren't many "optional" certifications, being qualified on multiple types of locomotives (e.g., AC vs. DC traction, different models from EMD and GE) makes you a more versatile and valuable employee for the railroad.

### 6. Level of Education (and its Limited Role)

Uniquely among high-paying professions, the level of formal education has a very limited direct impact on a railroad engineer's salary.

- Minimum Requirement: The standard requirement is a high school diploma or GED.

- The Real "Education": The critical education is the intensive company-sponsored training. This is where you learn the rules, regulations, and hands-on skills. This training, which can last for months, is paid, and passing it is the true barrier to entry.

- College Degrees: A bachelor's degree in logistics, transportation, or business management is not required and will not give you a higher starting salary as an engineer. However, it can become a significant advantage if you later decide to move from an operational role into a management position, such as a Road Foreman of Engines, Trainmaster, or a corporate logistics role. For the role of operating the locomotive itself, the railroad values demonstrated skill and seniority above all else.

---

Job Outlook and Career Growth

For anyone considering a long-term commitment to the rails, understanding the future stability and advancement potential of the profession is just as important as the initial salary. The career of a railroad engineer offers a unique mix of stability, technological evolution, and a clearly defined path for advancement, albeit with slower overall industry growth.

Official Job Outlook Analysis