Introduction

For those who feel an unshakeable connection to the natural world, who see the intricate dance of ecosystems and feel a calling to protect it, the career of a conservation biologist is more than just a job—it's a mission. It’s a path for individuals driven by a desire to study, manage, and preserve the biodiversity of our planet, from the smallest insects to the largest whales, and the habitats they call home. But passion, while essential, doesn't pay the bills. A crucial question for any aspiring professional is: Can I build a sustainable and rewarding life on a conservation biologist salary?

The answer is a resounding yes, but it comes with nuance. The financial landscape for a conservation biologist is complex and varied. While this career may not lead to the high-six-figure salaries common in finance or technology, it offers a stable, professional income that grows significantly with expertise and strategic career choices. The national median salary for zoologists and wildlife biologists, the category under which conservation biologists are classified, is $70,610 per year, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). However, this single number only tells part of the story. Entry-level positions may start closer to $45,000, while senior scientists, program directors, and specialized consultants can earn well over $100,000.

I once had the privilege of speaking with a senior biologist for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service who had spent three decades working on endangered species recovery. She spoke not of the salary, but of the profound satisfaction of seeing a species she had monitored for years, like the California Condor, slowly return from the brink of extinction. This blend of tangible impact and professional stability is the true hallmark of a career in conservation biology.

This guide is designed to be your definitive resource for understanding the conservation biologist salary. We will dissect the data, explore every factor that influences your earning potential, and provide a clear, actionable roadmap to help you not only enter this vital field but also thrive within it.

### Table of Contents

- [What Does a Conservation Biologist Do?](#what-does-a-conservation-biologist-do)

- [Average Conservation Biologist Salary: A Deep Dive](#average-conservation-biologist-salary-a-deep-dive)

- [Key Factors That Influence Salary](#key-factors-that-influence-salary)

- [Job Outlook and Career Growth](#job-outlook-and-career-growth)

- [How to Get Started in This Career](#how-to-get-started-in-this-career)

- [Conclusion](#conclusion)

What Does a Conservation Biologist Do?

Before we delve into the numbers, it's essential to understand the multifaceted nature of the role itself. A conservation biologist is a scientist who works at the intersection of ecology, genetics, policy, and resource management to protect biodiversity. Their work is fundamentally problem-oriented, seeking to understand the threats facing species and ecosystems—such as habitat loss, climate change, pollution, and invasive species—and to develop and implement solutions.

The profession is far from monolithic; the day-to-day responsibilities can vary dramatically depending on the employer, specialization, and specific project. However, the core duties generally revolve around a few key areas:

- Research and Data Collection (Fieldwork): This is the classic image of a biologist: out in nature, collecting data. This can involve conducting population surveys of animals or plants, tracking animal movements with GPS collars, collecting genetic samples (like fur, feathers, or feces), taking water or soil samples for analysis, and assessing habitat quality. This work can be physically demanding, requiring long hours in remote, sometimes harsh, conditions.

- Data Analysis and Modeling (Lab and Office Work): The raw data collected in the field is useless without analysis. Biologists spend a significant amount of time in the office or lab using statistical software (like R or Python) and geographic information systems (GIS) to analyze population trends, map habitats, model the effects of climate change, and identify conservation priorities. Lab work might involve genetic analysis to understand population health and diversity.

- Reporting and Communication: A critical, often underestimated, part of the job is communicating findings. This includes writing detailed technical reports for government agencies, preparing manuscripts for publication in peer-reviewed scientific journals, creating management plans, and writing grant proposals to secure funding for future research.

- Policy and Management: Conservation doesn't happen in a vacuum. Biologists often work with government agencies, non-profit organizations, and private landowners to translate scientific findings into on-the-ground action. This could mean advising on land use policy, helping to design a new national park, developing recovery plans for endangered species, or managing invasive species removal programs.

- Public Outreach and Education: Many conservation biologists are passionate advocates for nature and engage in public outreach. This can involve giving presentations to community groups, developing educational materials for schools, speaking with journalists, or working with citizen science programs to engage the public in data collection.

### A Day in the Life: Dr. Elena Ramirez, Marine Conservation Biologist

To make this more tangible, let's imagine a day in the life of a mid-career marine conservation biologist working for a state environmental agency.

- 6:00 AM: Elena’s day starts early. She and a small team load their gear onto a research vessel. Today, they are heading out to a coastal estuary to monitor the health of seagrass beds, a critical habitat for juvenile fish and a key indicator of water quality.

- 8:00 AM - 1:00 PM: On the water, the team uses a combination of drone imagery and underwater transects. Elena operates the drone to capture high-resolution aerial photos for habitat mapping. Afterwards, she and a technician don their dive gear to swim along pre-set lines (transects), recording the species, density, and health of the seagrass. They also collect water samples to test for nutrient levels back at the lab.

- 1:00 PM - 2:30 PM: Back on shore, the team unloads and cleans the gear. Elena meticulously labels and stores the water samples for processing.

- 2:30 PM - 5:00 PM: The afternoon is spent at the office. Elena uploads the drone imagery and begins processing it with GIS software to measure changes in the seagrass meadow's size since the last survey. She enters the data from the dive transects into a shared database and performs a preliminary statistical analysis.

- 5:00 PM - 6:00 PM: Elena spends the last hour of her day working on a grant proposal. The current project's funding is set to expire in six months, and securing a new grant is crucial to continue their monitoring efforts. She reviews the budget, refines the project narrative, and emails a collaborator at a local university to get their feedback.

This example illustrates the dynamic blend of fieldwork, technical analysis, and administrative responsibility that defines the career. It is a demanding but deeply varied profession.

Average Conservation Biologist Salary: A Deep Dive

Understanding compensation in conservation biology requires looking beyond a single average. The salary spectrum is wide, influenced by a host of factors we'll explore in the next section. Here, we'll establish a baseline by examining national averages, typical ranges, and how salary progresses with experience.

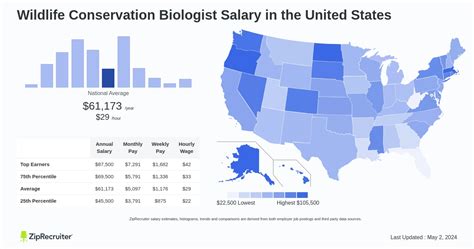

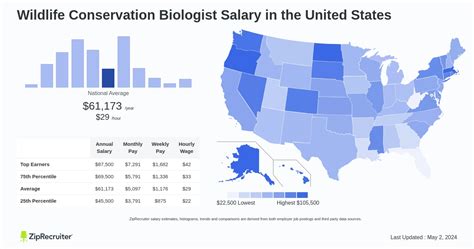

### National Averages and Ranges

The most reliable source for occupational data in the United States is the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). The BLS groups conservation biologists under the broader category of "Zoologists and Wildlife Biologists."

- Median Annual Salary: The median salary was $70,610 per year as of May 2023. This means that half of all professionals in this field earned more than this amount, and half earned less.

- Salary Range: The BLS also provides a percentile range, which gives a more complete picture:

- Lowest 10%: Earned less than $46,440

- Highest 10%: Earned more than $108,010

This BLS data provides a solid, authoritative foundation. To add more granularity, we can look at data from reputable salary aggregators, which often collect real-time, self-reported data.

- Payscale.com reports the average salary for a "Conservation Biologist" specifically as approximately $60,400 per year, with a typical range falling between $45,000 and $86,000.

- Salary.com lists the median salary for a "Wildlife Biologist" as $68,895, with the main salary band typically ranging from $58,688 to $81,598.

- Glassdoor.com estimates the total pay for a "Conservation Scientist" to be around $77,000 per year, including a base salary of about $66,000 and additional pay (like bonuses) of about $11,000.

Synthesis: Combining these sources, a realistic salary expectation for a conservation biologist in the U.S. is a median figure in the $68,000 to $71,000 range. The vast majority of positions will fall within a broader range of $45,000 to $95,000, with the lowest end representing entry-level technician roles and the highest end representing senior scientists, managers, or specialized consultants.

### Salary by Experience Level

Experience is arguably the single most powerful driver of salary growth in this field. As you accumulate skills, manage larger projects, and build a professional reputation, your earning potential increases significantly. Here is a typical salary trajectory, compiled from Payscale and Salary.com data:

| Career Stage | Typical Years of Experience | Average Annual Salary Range | Key Responsibilities & Role |

| :--- | :--- | :--- | :--- |

| Entry-Level | 0-2 Years | $45,000 - $58,000 | Assisting with fieldwork, data entry, lab assistance. Often seasonal or temporary technician roles. |

| Early-Career | 2-5 Years | $55,000 - $68,000 | Leading small field crews, conducting independent data analysis, co-authoring reports, managing smaller projects. |

| Mid-Career | 5-10 Years | $65,000 - $80,000 | Project management, primary author on reports/publications, supervising junior staff, grant writing, advising on policy. |

| Senior/Experienced | 10-20 Years | $78,000 - $95,000 | Program Director, Principal Investigator (PI) on major grants, setting strategic conservation priorities, senior policy advisor. |

| Late-Career/Expert | 20+ Years | $90,000 - $110,000+ | Senior leadership roles (e.g., Chief Scientist, Regional Director), high-level consulting, tenured full professor at a major university. |

*(Note: These are national averages. Actual salaries can be higher or lower based on the factors discussed in the next section.)*

### Beyond the Base Salary: Understanding Total Compensation

Your salary is just one piece of your total compensation package. It's crucial to evaluate the entire offer, as benefits can add significant value, particularly in government and non-profit roles.

- Bonuses and Profit Sharing: These are more common in the private environmental consulting sector than in government or non-profit work. They are typically tied to company performance or meeting project-specific targets.

- Health Insurance: Government agencies and large non-profits usually offer excellent, comprehensive health, dental, and vision insurance plans, often with lower premiums than those found in the private sector for similar coverage. This can be worth thousands of dollars annually.

- Retirement Plans:

- Federal Government: Employees participate in the Federal Employees Retirement System (FERS), a three-tiered plan that includes a Basic Benefit Plan (pension), Social Security, and the Thrift Savings Plan (TSP), which is a 401(k)-style plan with a generous government match (up to 5%). This is one of the best retirement packages available.

- Non-Profits & Academia: Typically offer 403(b) or 401(k) plans with varying levels of employer matching.

- Paid Time Off (PTO): Government roles often have structured and generous leave policies (vacation, sick leave, and federal holidays) that increase with years of service.

- Per Diem and Field Allowances: For roles involving extensive travel or fieldwork, employers often provide a "per diem"—a daily allowance to cover lodging, food, and incidental expenses. This is not salary but significantly reduces personal costs while on assignment.

- Professional Development Funds: Many employers encourage continuous learning and will provide a budget for attending scientific conferences, taking specialized training courses (like a GIS workshop), or renewing professional certifications.

- Grant-Funded Salary: In academia, a professor's salary is often a combination of a "hard money" base salary from the university and "soft money" from research grants they secure. A successful grant writer can significantly augment their income.

When comparing job offers, always look at the total value of the compensation package, not just the base salary figure. A government job with a slightly lower salary but a superior pension and health plan might be more valuable in the long run than a private sector job with a higher starting wage but fewer benefits.

Key Factors That Influence Salary

The wide salary ranges discussed above are a direct result of several key variables. A conservation biologist with a Ph.D., 15 years of experience, specialized GIS skills, working for the federal government in California will earn vastly more than an entry-level technician with a bachelor's degree working for a small non-profit in the rural South. Understanding these factors is critical for maximizing your own earning potential.

###

1. Level of Education

In a science-driven field like conservation, education is the bedrock of your career and a primary determinant of your starting salary and long-term ceiling.

- Bachelor's Degree (B.S. or B.A.): A bachelor's degree in biology, ecology, environmental science, zoology, or a related field is the minimum requirement to enter the profession. With a B.S., you can qualify for entry-level positions such as a Biological Technician, Field Assistant, or Research Aide. These roles are often seasonal or contract-based and fall at the lower end of the salary spectrum ($40,000 - $55,000). A bachelor's degree is a starting point, but upward mobility and access to higher-paying roles are often limited without further education.

- Master's Degree (M.S.): A master's degree is often considered the "workhorse" degree for a professional conservation biologist. It signals a higher level of specialized knowledge, research experience, and analytical skill. An M.S. is frequently the minimum qualification for permanent Biologist or Conservation Scientist positions with state and federal agencies and larger non-profits. It opens the door to project management responsibilities and unlocks a significant salary increase, often placing individuals in the $60,000 - $75,000 range even in early to mid-career stages. The two years spent obtaining an M.S. typically have a very high return on investment in this field.

- Doctorate (Ph.D.): A Ph.D. is the highest level of academic achievement and is essential for certain career paths. It is a prerequisite for becoming a tenured university professor, leading a research lab, or holding a high-level Principal Investigator (PI) or Senior Scientist position at a government agency (e.g., USGS, NOAA) or major research institution. These roles command the highest salaries in the field, often reaching $90,000 to well over $100,000. However, a Ph.D. is a long commitment (typically 4-6 years post-bachelor's) and often involves several years in lower-paid postdoctoral research positions ($50,000 - $65,000) before securing a permanent, high-paying role. It is a path for those deeply committed to leading independent research.

- Certifications: While not a substitute for a degree, professional certifications can enhance your resume and increase your value. Certifications in Geographic Information Systems (GISP), project management (PMP), or specialized skills like Wilderness First Responder (WFR) or Certified Drone Pilot can make you a more competitive candidate and potentially lead to higher pay or specialized roles.

###

2. Years of Experience

As detailed in the previous section, experience is a powerful salary driver. It's not just about the number of years but the quality and nature of that experience.

- 0-2 Years (Entry-Level): Focus is on gaining fundamental skills. Pay is lower because your role is primarily supportive. The value you gain is in experience, not income. Many start with multiple temporary jobs, like summer field seasons for different agencies, to build a diverse resume.

- 2-5 Years (Early-Career): You have proven your basic competence. Employers trust you to work more independently and even lead small teams. You transition from a technician to a biologist. This is where the first significant salary jump occurs, often after completing a Master's degree.

- 5-10 Years (Mid-Career): You are now a subject matter expert. You are not just collecting data; you are designing the studies, managing the budgets, writing the final reports, and mentoring junior staff. Your salary reflects this increased responsibility and expertise.

- 10+ Years (Senior/Leadership): Your value is now strategic. You are responsible for entire programs, securing multi-million dollar grants, shaping agency policy, and representing your organization to the public and other stakeholders. Your deep institutional knowledge and extensive professional network are invaluable, and your compensation reflects this top-tier status.

###

3. Geographic Location

Where you work has a dramatic impact on your paycheck. This variation is driven by the cost of living, the concentration of employers (particularly federal agencies), and state-level funding for conservation.

High-Paying States and Regions:

- Washington, D.C. & Surrounding Area (Maryland, Virginia): This region is the epicenter of federal government work. The headquarters for agencies like NOAA, USGS, and the EPA, as well as major non-profits like The Nature Conservancy and World Wildlife Fund, are located here. The concentration of high-level policy and research jobs leads to higher average salaries, often adjusted for the high cost of living. A mid-career federal biologist (GS-12) in the D.C. area can earn $99,200 - $128,956 (2024 pay scale).

- California: With a high cost of living, strong state environmental regulations, and numerous federal and state agencies, California offers some of the highest salaries in the nation. Biologists here work on a vast range of issues, from marine conservation along the coast to forest management in the Sierra Nevada. Average salaries often exceed $85,000.

- Alaska: The unique and vast ecosystems, coupled with a large federal presence (NPS, USFWS, BLM) and a significant oil and gas industry requiring environmental consultants, drive up salaries. A cost-of-living adjustment (COLA) is often applied to federal salaries, further boosting pay.

- Colorado: Denver and Boulder are major hubs for federal agencies (USGS, USFWS, Forest Service) and prominent non-profits. The state's focus on wildlife management and outdoor recreation supports numerous well-paid biologist positions.

- Northeast (e.g., Massachusetts, New York): Strong state environmental agencies, numerous universities, and a high cost of living contribute to higher-than-average salaries, particularly in coastal and marine conservation.

Lower-Paying States and Regions:

- The Southeast (e.g., Mississippi, Arkansas, Alabama): While rich in biodiversity, these states generally have a lower cost of living and lower state budgets for environmental programs, which translates to more modest salaries, often in the $50,000 - $65,000 range for experienced professionals.

- The Midwest: Similar to the Southeast, many Midwestern states offer lower average salaries due to a lower cost of living and fewer large federal research centers compared to the coasts.

*(Source: Data for regional salary differences can be found in the BLS Occupational Employment and Wage Statistics (OEWS) which provides state-by-state data for Zoologists and Wildlife Biologists.)*

###

4. Employer Type and Sector

The type of organization you work for is a massive factor in your salary and overall career path.

- Federal Government: This is often seen as the gold standard for stability, benefits, and clear career progression. Agencies like the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), National Park Service (NPS), U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), NOAA Fisheries, Bureau of Land Management (BLM), and the U.S. Forest Service (USFS) are the largest employers of conservation biologists. Salaries are determined by the transparent General Schedule (GS) pay scale.

- Entry-Level (B.S.): GS-5 or GS-7 (approx. $34k - $53k, depending on location)

- Master's Degree: GS-9 (approx. $53k - $69k)

- Ph.D. or Experienced M.S.: GS-11 or GS-12 (approx. $64k - $99k)

- Senior/Managerial: GS-13, GS-14, GS-15 (approx. $94k - $167k+)

- State Government: State-level Departments of Fish and Wildlife, Natural Resources, or Environmental Protection are also major employers. Salaries are highly variable by state. They are typically lower than federal salaries for equivalent roles but offer good job security and benefits.

- Non-Profit Organizations (NGOs): This sector includes a vast range of organizations, from huge international players like The Nature Conservancy (TNC) and the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) to small, local land trusts. Passion and mission are the primary drivers here. Salaries at large NGOs can be competitive with government roles, especially at senior levels. However, at smaller, grassroots organizations, salaries are often significantly lower due to tighter budgets.

- Academia (Universities and Colleges): For those with a Ph.D., a tenure-track professorship offers a path of teaching, research, and service. Salaries vary widely based on the institution's size and endowment (e.g., a professor at an R1 university like Stanford will earn far more than one at a small liberal arts college). Postdoctoral positions are a necessary stepping stone but are temporarily low-paid. A tenured full professor at a major research university can earn $100,000 - $180,000+.

- Private Sector (Environmental Consulting): This can be the most lucrative sector. Private firms are hired by companies or government agencies to conduct environmental impact assessments, ensure regulatory compliance (e.g., for construction projects), and develop mitigation plans. Biologists with specialized, in-demand skills can earn high salaries, but the work can be high-pressure