Table of Contents

- [What Does a Wildlife Veterinarian Do?](#what-does-a-wildlife-veterinarian-do)

- [Average Wildlife Veterinarian Salary: A Deep Dive](#average-wildlife-veterinarian-salary-a-deep-dive)

- [Key Factors That Influence a Wildlife Veterinarian's Salary](#key-factors-that-influence-a-wildlife-veterinarians-salary)

- [Job Outlook and Career Growth for Wildlife Vets](#job-outlook-and-career-growth-for-wildlife-vets)

- [How to Become a Wildlife Veterinarian: Your Step-by-Step Guide](#how-to-become-a-wildlife-veterinarian-your-step-by-step-guide)

- [Conclusion: Is a Career as a Wildlife Vet Right for You?](#conclusion-is-a-career-as-a-wildlife-vet-right-for-you)

The image is powerful and universal: a dedicated veterinarian treating a majestic, untamed creature—a tranquilized lion, an injured eagle, a sick sea turtle. It’s a career that calls to those with a profound love for animals and an unshakeable commitment to conservation. But beyond the undeniable passion and adventure, a crucial question remains for anyone considering this demanding path: what is the reality of a wild animal vet salary? This career is often misunderstood as being either a low-paying volunteer-style role or a glamorous, high-earning globetrotting adventure. The truth, as is often the case, lies somewhere in the middle and is shaped by a complex interplay of factors.

This comprehensive guide will demystify the financial realities of this profession. While the median salary for all veterinarians in the United States is a robust $103,260 per year (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2022), the niche of wildlife, zoo, and conservation medicine presents a much wider and more varied spectrum. Salaries can range from a modest $60,000 for an entry-level position at a small rehabilitation center to well over $150,000 for a board-certified, experienced veterinarian at a major metropolitan zoo or a federal agency.

I once had the privilege of speaking with a senior zoo veterinarian who was overseeing a complex dental procedure on a silverback gorilla. Between monitoring anesthesia and directing her team, she told me, "People see the incredible moments, but they don't see the decades of study, the crushing student debt, the 2 a.m. emergency calls, or the grant applications we write to fund it all. You don't do this for the money, but you absolutely have to be able to make a living doing it." Her words capture the essence of this guide: to provide a clear, authoritative, and realistic look at the financial and professional journey of a wildlife veterinarian, empowering you to pursue your passion with your eyes wide open.

---

What Does a Wildlife Veterinarian Do?

While the title "wild animal vet" evokes images of fieldwork and dramatic rescues, the reality of the profession is far more diverse and scientifically rigorous. A wildlife veterinarian, also known as a zoological or conservation veterinarian, is a medical professional dedicated to the health and welfare of non-domesticated animals. Their "patients" can range from the megafauna of a zoo collection—elephants, giraffes, and bears—to entire populations of free-ranging animals like deer, birds of prey, or marine mammals.

Their core mission is multifaceted, blending individual animal medicine with population health, research, and public education. It is a far cry from the predictable schedule of a small animal clinic that treats cats and dogs. The responsibilities of a wildlife vet are dictated by their specific employer, be it a zoo, an aquarium, a government agency, a university, or a non-profit conservation organization.

Core Responsibilities and Daily Tasks Often Include:

- Clinical Medicine: Diagnosing and treating illnesses and injuries in individual animals. This involves everything from routine check-ups and vaccinations to complex surgeries, dentistry, and emergency care.

- Preventive Medicine & Herd Health: Developing and implementing comprehensive health programs for an entire collection or population. This includes quarantine protocols for new animals, parasite control, nutritional planning, and disease surveillance to prevent outbreaks.

- Anesthesia and Immobilization: Safely anesthetizing animals for examinations, transport, or medical procedures. This is a high-stakes skill requiring deep knowledge of the unique physiology of hundreds of different species, often administered via remote darting systems.

- Research and Conservation: Conducting or participating in research projects that advance our understanding of wildlife diseases, reproductive biology, and conservation strategies. Their findings are often published and contribute directly to global efforts to protect endangered species.

- Pathology and Necropsy: Performing post-mortem examinations (necropsies) to determine the cause of death. This is a critical tool for monitoring disease trends and understanding threats to animal populations.

- Regulatory Compliance and Husbandry: Working closely with animal curators and keepers to ensure that animal habitats, diets, and enrichment programs meet the highest standards of welfare and comply with federal regulations like the Animal Welfare Act.

- Public Education and Communication: Acting as a scientific authority and educator, speaking to the public, donors, and media about animal health and conservation issues.

### A Day in the Life of a Zoo Veterinarian

To make this tangible, consider a hypothetical "typical" day for a veterinarian at a large zoo:

- 8:00 AM - Morning Rounds: The day begins with a meeting with the hospital's veterinary technicians and the zoo's curators. They discuss any overnight issues, review cases, and plan the day's procedures. An elderly snow leopard is reported to be lethargic and not eating.

- 9:00 AM - Anesthetic Procedure: The team prepares for an examination of the snow leopard. The vet calculates the precise drug dosage for chemical immobilization and successfully darts the animal. Once it's safely anesthetized, the team moves it to the hospital.

- 9:45 AM - Diagnostics: In the hospital, the vet and technicians work efficiently. They draw blood for analysis, take radiographs (X-rays) to check for internal issues, and perform an ultrasound of its abdomen. They also use the opportunity to conduct a full physical, checking its teeth, eyes, and joints.

- 11:30 AM - Lab Work & Consultation: While the leopard recovers from anesthesia under careful monitoring, the vet analyzes the bloodwork and radiographs. The results suggest kidney disease, a common ailment in older felines. She consults with the zoo's nutritionist to formulate a new diet and prescribes medication to manage the condition.

- 1:00 PM - Administrative Work: Lunch is often at the desk while catching up on emails, updating medical records, and reviewing lab results from other cases. She spends an hour writing a section of a grant proposal to fund a new conservation project.

- 2:30 PM - Field Call: A call comes in from the hoofstock keepers. A newborn gazelle appears weak and isn't nursing. The vet drives to the habitat to examine the calf, provide subcutaneous fluids, and assist the keepers in bottle-feeding attempts.

- 4:00 PM - Quarantine Check: The vet visits the quarantine facility to perform a routine health check on a group of tamarin monkeys that recently arrived from another zoo, ensuring they are free of disease before joining the main population.

- 5:30 PM - End of Day: The vet checks in on the snow leopard and the gazelle calf one last time before heading home—always with her phone on, prepared for an after-hours emergency.

This example illustrates the immense variety, intellectual challenge, and physical demands of the job. It is a career that requires not just medical skill, but also problem-solving, collaboration, and a deep, abiding resilience.

---

Average Wildlife Veterinarian Salary: A Deep Dive

Analyzing the salary of a wildlife veterinarian requires a nuanced approach. Unlike many standardized professions, compensation in this field doesn't follow a single, clear path. It is highly dependent on specialization, employer type, and experience. To build a complete picture, we must first look at the benchmark for all veterinarians and then drill down into the specifics of the zoological and conservation niche.

### The National Benchmark: All Veterinarians

The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) provides the most comprehensive data for the veterinary profession as a whole. According to its May 2022 Occupational Employment and Wage Statistics, the key figures for veterinarians are:

- Median Annual Wage: $103,260 (This means 50% of vets earned more than this, and 50% earned less).

- Mean Annual Wage: $126,540

- Salary Range:

- Lowest 10%: Earned less than $61,840

- Highest 10%: Earned more than $199,440

This data primarily reflects veterinarians in private clinical practice (treating companion animals and livestock), who make up the vast majority of the profession. While wildlife vets are included in this data, their specific salary landscape is different. They often trade the higher earning potential of private practice ownership for the unique opportunities and non-monetary rewards of working with exotic species.

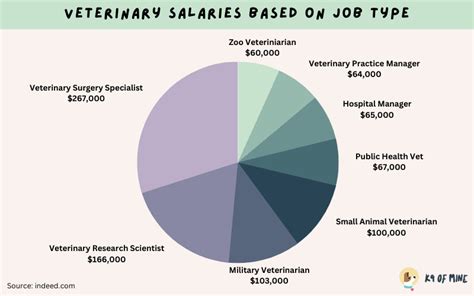

### Wildlife and Zoo Veterinarian Salary Specifics

Data for the specialized field of wildlife and zoo medicine is gathered by salary aggregators and professional associations. It consistently shows a slightly lower starting point than private practice but with a strong potential for growth, especially for those who achieve board certification.

Here’s a breakdown of what you can expect at different stages of your career, compiled from recent data from Salary.com, Payscale, and Glassdoor (data accessed November 2023).

| Career Stage | Typical Experience | Average Annual Salary Range | Notes |

| :--- | :--- | :--- | :--- |

| Entry-Level | 0-3 years (Post-DVM, often includes internship) | $60,000 - $85,000 | Often in internships, residencies, or roles at smaller non-profits, sanctuaries, or rehabilitation centers. |

| Mid-Career | 4-10 years (Staff Veterinarian) | $85,000 - $125,000 | Typically a staff veterinarian at a medium to large zoo, aquarium, or state wildlife agency. |

| Senior/Experienced | 10-20+ years (Senior Veterinarian) | $120,000 - $160,000+ | Senior roles, Head Veterinarian, or Veterinary Curator at major zoos, federal agencies, or in academia. |

| Board-Certified Specialist (Diplomate) | 10-20+ years + Certification | $140,000 - $200,000+ | Considered top experts in the field. Hold leadership positions, professorships, or director-level roles. |

*(Sources: Salary.com, Payscale.com, Glassdoor.com, ZipRecruiter, compiled November 2023. Ranges are estimates and can vary significantly.)*

As Salary.com reports, the average Zoo Veterinarian salary in the United States is $105,958 as of October 2023, but the range typically falls between $86,211 and $131,061. This aligns closely with the general veterinarian median but highlights the broad variability.

### Understanding Your Full Compensation Package

Base salary is only one part of the equation. The total compensation package for a wildlife vet, especially those employed by government agencies or large institutions, can be substantial.

- Bonuses and Profit Sharing: These are rare in the non-profit and government sectors that employ most wildlife vets. Unlike private practice, there is no "profit" to share. Performance-based bonuses are uncommon.

- Health and Retirement Benefits: This is a significant factor. Employment with government (federal or state) or large universities often comes with excellent benefits packages, including comprehensive health insurance, life insurance, and robust pension or retirement plans (e.g., 401(k) or 403(b) with employer matching). These benefits can add tens of thousands of dollars in value to the total compensation.

- Paid Time Off (PTO): Most full-time positions include standard vacation time, sick leave, and holidays.

- Continuing Education (CE) Stipend: Most reputable employers provide an annual allowance for veterinarians to attend conferences, workshops, and training courses to maintain their license and stay current in the field. This can be worth several thousand dollars per year.

- Professional Dues and Liability Insurance: Employers typically cover the cost of state licensing fees, membership in professional organizations (like the American Association of Zoo Veterinarians), and professional liability insurance.

- Unique Perks: While not monetary, some jobs come with unique benefits. A field conservationist may have housing provided in a remote location. A zoo vet may have access to the institution and special events. These intangible benefits are a major draw for many in the profession.

When evaluating a job offer, it's critical to look beyond the base salary and consider the total value of the compensation and benefits package. A slightly lower salary at an institution with a generous retirement plan and excellent health insurance may be more financially advantageous in the long run.

---

Key Factors That Influence a Wildlife Veterinarian's Salary

The wide salary ranges presented above are not arbitrary. A wildlife vet's earning potential is directly influenced by a handful of critical factors. For anyone aspiring to this career, understanding these levers is key to maximizing both professional impact and financial stability. This is the most important section for understanding the "why" behind the numbers.

### 1. Level of Education and Specialization

The educational path for a wildlife vet is long and demanding, and compensation directly reflects the level of training achieved.

- Doctor of Veterinary Medicine (DVM): This is the non-negotiable foundation. A DVM degree is required to practice veterinary medicine in the United States. A veterinarian fresh out of school with a DVM is at the starting point of the salary spectrum.

- Internship (1-Year Post-DVM): Most aspiring zoo and wildlife vets undertake a competitive one-year rotating or specialty internship after their DVM. These are low-paying positions (often in the $35,000 - $50,000 range) but are considered essential stepping stones. They provide invaluable hands-on experience that is a prerequisite for most residency programs and jobs.

- Residency (3-Year Specialized Training): This is the most significant educational step for increasing earning potential. A residency is an intensive, three-year program focused on a specific area, such as zoological medicine. Residents are paid a modest stipend (typically $45,000 - $65,000) while they train under the supervision of board-certified specialists. Completing a residency is the primary pathway to becoming a specialist.

- Board Certification (Diplomate Status): This is the pinnacle of specialization. After completing a residency, a veterinarian is eligible to take a rigorous examination administered by a specialty college, such as the American College of Zoological Medicine (ACZM). Earning the title "Diplomate" signifies the highest level of expertise. Board-certified specialists command the highest salaries in the field, often exceeding $150,000 - $200,000, and are sought for top leadership positions.

- Advanced Degrees (MS, PhD): Some wildlife vets also pursue a Master of Science (MS) or a PhD, particularly if their career goals are focused on research, epidemiology, or academia. A DVM/PhD dual degree can be a powerful combination for securing high-level research positions at universities or government agencies like the CDC or USDA, often with salaries competitive with top clinical specialists.

### 2. Years of Experience

As with any profession, experience is a primary driver of salary growth. In wildlife medicine, experience translates to a broader knowledge base of species, a proven track record of handling complex cases, and refined surgical and diagnostic skills.

- Entry-Level (0-3 Years): This stage typically includes interns, residents, and associate veterinarians in their first job post-residency. They are building their skills and confidence under supervision. Salaries are at the lower end of the spectrum, reflecting their status as learners.

- Mid-Career (4-10 Years): A veterinarian at this stage has completed their specialized training and is a competent, independent practitioner. They are the workhorses of most zoo and wildlife health departments. Their salary sees a significant jump from the training years, settling into the national average range of $85,000 to $125,000.

- Senior/Experienced (10-20+ Years): After a decade or more, veterinarians become senior staff members. They mentor junior vets, take on more complex cases, and may have administrative duties. Their deep institutional and species-specific knowledge makes them invaluable. Salaries for senior vets push into the $120,000 to $160,000+ range.

- Leadership/Director Roles (15+ Years): The most experienced professionals may advance to leadership roles like Head of Veterinary Services, Vice President of Animal Health, or Veterinary Curator. These roles involve managing budgets, staff, and entire departmental strategies, and their compensation reflects these significant responsibilities, often reaching the highest end of the salary scale.

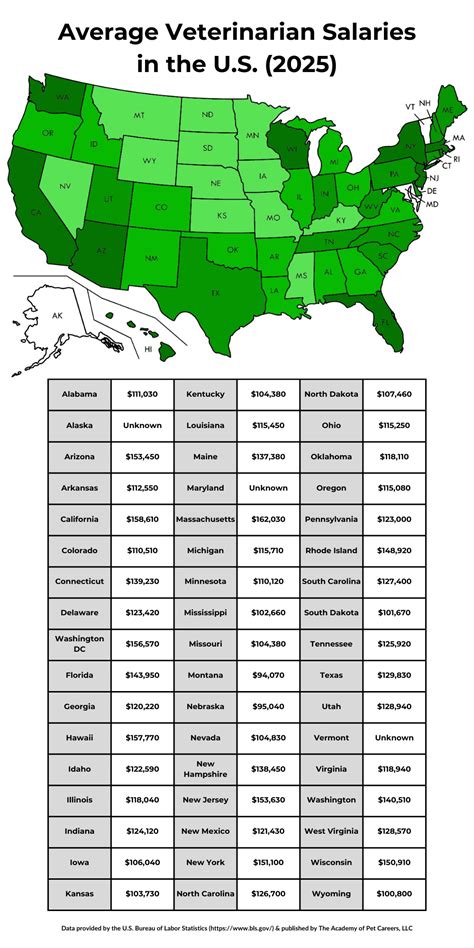

### 3. Geographic Location

Where you work in the country has a profound impact on your salary, driven by cost of living and the concentration of relevant employers.

- High-Paying States and Metropolitan Areas: Salaries are typically highest in areas with a high cost of living and the presence of large, well-funded zoos, aquariums, or federal agency headquarters. According to data analysis, states like California, Florida, Illinois, New York, and the Washington D.C. metro area often offer higher salaries. For example, a zoo veterinarian in San Diego or Chicago will likely earn significantly more than one in a smaller Midwestern city.

- Lower-Paying States and Rural Areas: States with a lower cost of living and fewer large zoological institutions will naturally have lower average salaries. Furthermore, many field conservation jobs are located in rural or remote areas. While the base salary for a state wildlife biologist in Montana or a research vet in a national park might be lower, it's often offset by a much lower cost of living and unique lifestyle benefits.

- International Opportunities: Working abroad presents an entirely different financial picture. A position with a conservation NGO in Southeast Asia or Africa may come with a modest salary but include housing, a vehicle, and travel expenses. A job at a state-of-the-art zoo in the United Arab Emirates or Singapore, however, could be exceptionally lucrative, with high, often tax-free salaries and generous benefits packages.

### 4. Employer Type and Size

The type of organization a wildlife vet works for is arguably the single biggest determinant of their salary and work environment.

- Large, AZA-Accredited Zoos and Aquariums: Major institutions like the San Diego Zoo, Bronx Zoo, Shedd Aquarium, or Georgia Aquarium are the top employers. They have larger budgets, more extensive facilities, and are more likely to employ multiple board-certified specialists. They offer the most competitive salaries and benefits packages, typically falling in the mid-to-high end of the ranges discussed.

- Federal Government: Agencies like the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), and the National Park Service (NPS) employ wildlife veterinarians as epidemiologists, field biologists, and policy advisors. Salaries are determined by the General Schedule (GS) pay scale, which is public and transparent. A DVM with a PhD might enter at a GS-12 or GS-13 level, which in 2023 could range from approximately $80,000 to $125,000 depending on location and experience, with a clear path for advancement to GS-14 or GS-15, where salaries can exceed $170,000.

- State Agencies: State-level Departments of Fish and Wildlife or Natural Resources employ veterinarians to manage the health of game populations (like deer, elk, and bears) and investigate disease outbreaks. These salaries are often lower than federal or large zoo positions but offer stable government employment and benefits.

- Academia (Universities): Veterinarians working at universities with veterinary schools hold faculty positions. Their work is a mix of teaching, research, and clinical service. Salaries are highly variable and depend on rank (Assistant, Associate, or Full Professor) and a professor's ability to secure research grants, which can supplement their income.

- Non-Profits and Sanctuaries: This is the most variable category. Smaller, private wildlife rehabilitation centers or animal sanctuaries often operate on tight budgets and rely heavily on donations. Salaries here are typically on the lowest end of the spectrum ($60,000 - $80,000), and the work is often a true labor of love. In contrast, large international conservation NGOs (like the Wildlife Conservation Society or World Wildlife Fund) may offer competitive salaries for high-level director or field project leader roles.

### 5. In-Demand Skills and Specializations

Beyond formal board certification, certain skills and sub-specialties can enhance a vet's value and earning potential.

- Aquatic and Marine Mammal Medicine: This is a highly specialized and challenging niche. Veterinarians with expertise in treating dolphins, sea lions, sea turtles, and fish are in demand at aquariums and marine mammal rescue centers, and this specialization can command a higher salary.

- Epidemiology and Population Health: With growing concerns about zoonotic diseases (diseases that jump from animals to humans) and threats like Chronic Wasting Disease, veterinarians with advanced skills in epidemiology and data analysis are highly valued by government agencies and research institutions.

- Anesthesiology and Pain Management: Expertise in advanced anesthesia protocols for high-risk or mega-vertebrate species is a critical skill that adds significant value to any zoological team.

- Grant Writing and Fundraising: Especially in academia and the non-profit world, the ability to secure funding through grant writing is a highly prized skill that can directly impact a vet's research opportunities and, in some cases, their salary.

- Pathology: Specializing in wildlife pathology—determining cause of death and diagnosing disease from tissue samples—is another critical and well-compensated niche within the field.

---

Job Outlook and Career Growth for Wildlife Vets

When considering a long and expensive educational path, the future job market is a paramount concern. The outlook for veterinarians, in general, is exceptionally strong, but the niche of wildlife medicine has its own unique dynamics of high demand for skills but intense competition for positions.

### The Broader Veterinary Job Market

According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) Occupational Outlook Handbook, employment for veterinarians is projected to grow 19 percent from 2022 to 2032. This is much faster than the average for all occupations. The BLS projects about 5,000 openings for veterinarians each year, on average, over the decade.

This incredible growth is primarily driven by:

1. Increased Spending on Companion Animals: While this is the main driver for the profession as a whole, it has a positive ripple effect. A strong veterinary market means more robust vet schools, more research funding, and a healthier overall profession.

2. A Limited Number of Graduates: There are only 33 accredited veterinary schools in the United States. The limited number of new veterinarians graduating each year compared to the high demand for their services creates a favorable job market for graduates.

3. High Attrition and Retirement: A significant number of veterinarians are approaching retirement age, which will create more openings for new professionals to fill.

### The Competitive Niche of Wildlife Medicine

While the overall market is booming, it is crucial to understand that the field of zoo and wildlife medicine represents a very small fraction of all veterinary jobs. The American Association of Zoo Veterinarians (AAZV) has approximately 1,200 members, a small number compared to the over 120,000 veterinarians in the U.S.

This creates a highly competitive environment. For every open internship, residency, or staff veterinarian position at a major zoo, there are often dozens, if not hundreds, of highly qualified applicants. Securing a coveted position is not just about getting a DVM; it's about excelling in vet school, gaining extensive pre-veterinary experience, and successfully navigating the competitive post-graduate training pipeline.

### Emerging Trends and Future Challenges

The role of the wildlife veterinarian is evolving, shaped by pressing global challenges and scientific advancements. Staying ahead of these trends is key to long-term career growth and relevance.

- The "One Health" Initiative: This is perhaps the most significant trend. "One Health" is the concept that human health, animal health, and environmental health are inextricably linked. The COVID-19 pandemic, a zoonotic disease, brought this concept into sharp focus. Wildlife veterinarians are on the front lines of monitoring diseases in animal populations that could pose a threat to humans. This has increased demand for vets with expertise in epidemiology, pathology, and public health at agencies like the CDC and USDA.

- Climate Change and Conservation: As habitats shift and ecosystems are stressed by climate change, wildlife populations face new threats, from new diseases to food scarcity. Wildlife veterinarians will play a critical role in managing the health of these vulnerable populations and developing strategies to help them adapt.

- Advanced Medical Technology: Just as in human medicine, veterinary medicine is benefiting from incredible technological leaps. CT scanners, MRIs, advanced surgical techniques, and sophisticated genetic analyses are becoming more common in top-tier zoos and research facilities. Vets who are adept at using these tools will be in high demand.

- Ethical and Welfare Concerns: Public awareness and scrutiny of animal welfare in zoos and aquariums are at an all-time high. Veterinarians are central to ensuring that the animals under their care are not just physically healthy, but are thriving with positive welfare states. Expertise in animal behavior and environmental enrichment is becoming increasingly important.

### How to Stay Relevant and Advance

Advancement in this field is not passive. It requires a continuous commitment to learning and professional development.

1. Pursue Board Certification: As highlighted earlier, becoming a Diplomate of the ACZM is the most direct path to leadership roles and higher salaries.

2. Never Stop Learning: Actively participate in continuing education. Attend major conferences like those hosted by the AAZV, the Wildlife Disease Association, and the American College of Veterinary Pathologists.

3. **Publish and