Introduction

Imagine a career at the apex of medical science, where intricate knowledge of human anatomy, unparalleled surgical skill, and profound empathy converge to restore mobility and alleviate chronic pain. This is the world of the orthopedic spine surgeon—a profession defined by its immense challenges, profound impact, and significant financial rewards. For those with the dedication and intellect to navigate its demanding path, the compensation reflects the stakes. The journey is long, but the potential to command an orthopedic spine surgeon salary that often exceeds $700,000 and can reach well into the seven figures makes it one of the most lucrative careers in all of medicine.

But this career is about far more than numbers. I once had a close friend, a vibrant former athlete, who was sidelined by a debilitating degenerative disc disease. He went from running marathons to barely being able to walk his dog. After a complex spinal fusion procedure, I witnessed his recovery firsthand—a slow but miraculous return to a life free from constant pain. The gratitude he felt for his spine surgeon was immeasurable, a testament to the life-changing power of this specialized field. This guide is for anyone inspired by that kind of impact, who is considering this demanding but incredibly rewarding path. We will delve deep into the financial realities, the influencing factors, and the step-by-step roadmap to becoming one of these elite medical professionals.

### Table of Contents

- [What Does an Orthopedic Spine Surgeon Do?](#what-does-an-orthopedic-spine-surgeon-do)

- [Average Orthopedic Spine Surgeon Salary: A Deep Dive](#average-orthopedic-spine-surgeon-salary-a-deep-dive)

- [Key Factors That Influence Salary](#key-factors-that-influence-salary)

- [Job Outlook and Career Growth](#job-outlook-and-career-growth)

- [How to Get Started in This Career](#how-to-get-started-in-this-career)

- [Conclusion](#conclusion)

---

What Does an Orthopedic Spine Surgeon Do?

An orthopedic spine surgeon is a highly specialized medical doctor (M.D. or D.O.) who has completed extensive training in both orthopedic surgery and the specific, complex anatomy of the spine. Their expertise lies in diagnosing and treating injuries, diseases, and deformities affecting the entire spinal column—from the cervical spine (neck) down to the lumbar and sacral spine (lower back).

While the term "surgeon" conjures images of the operating room, a significant portion of their work is non-operative. They are musculoskeletal experts first and foremost, focusing on the least invasive treatment plan that will be effective for the patient. Their primary responsibility is to restore function, reduce pain, and improve the quality of life for individuals suffering from a wide range of spinal conditions.

Core Responsibilities and Daily Tasks:

- Patient Consultation and Diagnosis: Conducting thorough physical examinations, reviewing patient histories, and interpreting advanced imaging studies like X-rays, CT scans, and MRIs to accurately diagnose spinal pathologies.

- Developing Treatment Plans: Creating comprehensive and individualized treatment strategies that may include non-operative care (physical therapy, medication, injections) or surgical intervention.

- Performing Complex Surgery: When surgery is necessary, they perform a variety of intricate procedures, such as:

- Spinal Fusion: Fusing two or more vertebrae together to eliminate painful motion.

- Laminectomy: Removing a portion of the vertebral bone (the lamina) to relieve pressure on the spinal cord or nerves.

- Discectomy: Removing a herniated or bulging disc.

- Deformity Correction: Performing complex reconstructions for conditions like scoliosis (curvature of the spine) or kyphosis (hunchback).

- Spinal Tumor Removal: Excising benign or malignant growths from the spinal column.

- Post-Operative Care: Managing patients' recovery after surgery, monitoring their progress, and adjusting treatment plans as needed to ensure optimal outcomes.

- Collaboration: Working closely with a multidisciplinary team of healthcare professionals, including physiatrists, neurologists, pain management specialists, physical therapists, and radiologists.

- Research and Education: Many spine surgeons, particularly in academic settings, are involved in clinical research to advance the field and teach medical students, residents, and fellows.

### A Day in the Life of a Spine Surgeon

To make this role more tangible, let's follow a hypothetical "OR day" for Dr. Evelyn Reed, a spine surgeon in private practice.

- 6:00 AM: Dr. Reed arrives at the hospital. She reviews the imaging and surgical plan for her first case, a two-level anterior cervical discectomy and fusion (ACDF) for a patient with severe nerve compression. She meets with the anesthesiologist and the surgical team to go over the plan and any potential concerns.

- 7:30 AM: The first surgery begins. For the next three hours, Dr. Reed works with meticulous precision, using a microscope to navigate the delicate structures of the neck, remove the damaged discs, and implant a bone graft and plate to stabilize the vertebrae.

- 10:30 AM: Surgery concludes successfully. Dr. Reed speaks with the patient's family, explaining that the procedure went as planned. She then dictates her operative notes while the team prepares the room for the next case.

- 11:30 AM: The second surgery, a lumbar laminectomy for spinal stenosis, begins. This procedure is less complex and takes about 90 minutes.

- 1:00 PM: After her second case, Dr. Reed grabs a quick lunch while making calls and responding to urgent emails. She also checks in on the patients she operated on the previous day, reviewing their progress with the hospitalist team.

- 2:00 PM: Dr. Reed heads to her office, which is in a building attached to the hospital. Her afternoon is filled with post-operative appointments. She sees patients who are two weeks, six weeks, and six months out from their surgeries, assessing their healing, reviewing new X-rays, and clearing them for activities like physical therapy.

- 5:00 PM: Her last patient leaves. She spends another hour completing patient charts, reviewing imaging for upcoming cases, and handling administrative tasks related to her practice.

- 6:30 PM: Dr. Reed leaves the hospital. The day has been long and demanding, both mentally and physically, but it ends with the knowledge that she has made a tangible difference in her patients' lives.

---

Average Orthopedic Spine Surgeon Salary: A Deep Dive

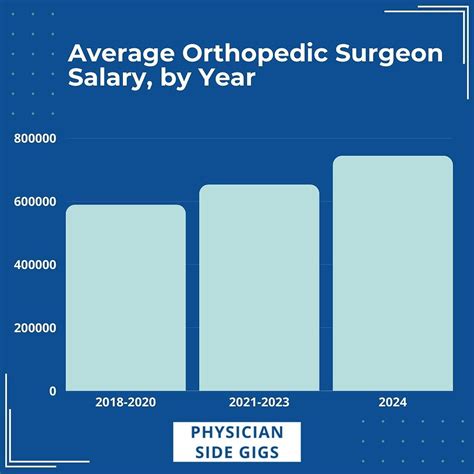

The orthopedic spine surgeon salary is consistently ranked among the highest in any profession, a direct reflection of the extensive training required, the high-stakes nature of the work, and the significant revenue these specialists generate for hospitals and private practices. Compensation is complex and multifaceted, comprising a base salary, productivity bonuses, and a range of other financial incentives.

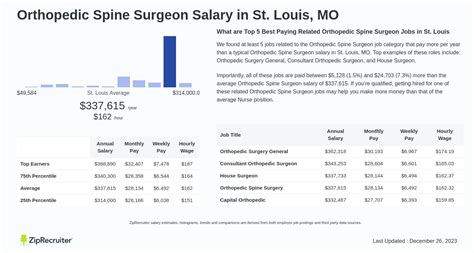

According to the most recent and authoritative industry reports, the national average salary for an orthopedic spine surgeon in the United States typically falls between $750,000 and $950,000 per year. However, this is just a midpoint, and the total compensation can vary dramatically.

- Doximity's 2023 Physician Compensation Report, one of the most comprehensive surveys in the industry, places orthopedic surgery as the second-highest paid specialty overall, with an average compensation of $654,815. It's critical to note that spine surgeons are a subspecialty *within* orthopedics and consistently earn significantly more than general orthopedists.

- Medscape's 2023 Physician Compensation Report shows an average salary for all orthopedists at $573,000. Again, spine-focused surgeons are at the top of this specialty's earning pyramid. Specific data for spine surgeons often points to figures 30-50% higher than the general orthopedic average.

- Salary aggregators provide a clearer picture of the range. Salary.com, as of late 2023, reports the median salary for a Spine Surgeon in the U.S. at $797,149, with a typical range falling between $521,291 and $1,117,140. This wide range highlights the powerful influence of factors like experience, location, and practice type.

### Salary Brackets by Experience Level

The earning potential of a spine surgeon grows substantially with experience. As surgeons build their reputation, perfect their techniques, and increase their surgical efficiency, their compensation rises accordingly.

| Experience Level | Typical Years of Practice | Average Annual Compensation Range | Key Characteristics |

| :--- | :--- | :--- | :--- |

| Entry-Level / Post-Fellowship | 0-3 Years | $450,000 - $650,000 | Often includes a guaranteed salary for the first 1-2 years. Lower productivity initially while building a practice and patient base. May receive a significant signing bonus. |

| Mid-Career | 4-15 Years | $700,000 - $1,200,000 | Fully productivity-based compensation (RVUs). Established reputation, strong referral network, and high surgical volume. Increased efficiency in the OR. |

| Senior / Late Career | 16+ Years | $800,000 - $1,500,000+ | Peak earning years. May hold leadership positions (e.g., Department Chair, Managing Partner). Potential for income from ancillary services, consulting, or expert witness work. |

*Note: These are representative ranges and can be influenced heavily by the factors discussed in the next section. Top earners in high-demand areas and efficient private practices can exceed these figures.*

### Deconstructing the Compensation Package

A spine surgeon's W-2 is rarely a single number. The total compensation package is a complex blend of different components:

- Base Salary: This is the guaranteed portion of a surgeon's income. In hospital-employed models, this might be a substantial, fixed amount. In private practice, it may be a more modest "draw" against future earnings. Many entry-level positions offer a high guaranteed base for the first one to two years before transitioning to a productivity model.

- Productivity Bonus (RVU-Based): This is the most significant part of most spine surgeons' income. Compensation is tied directly to the volume and complexity of the work performed. Each medical service and procedure is assigned a Relative Value Unit (RVU) by Medicare. Surgeons are often paid a specific dollar amount per wRVU (work RVU) they generate above a certain threshold. A busy spine surgeon can generate tens of thousands of wRVUs per year, leading to substantial bonus payments. For example, a complex spinal fusion might be worth 50-70 wRVUs, and a surgeon might be compensated at $60-$90 per wRVU.

- Signing Bonus: To attract top talent, especially in competitive markets, hospitals and large practices often offer substantial signing bonuses. For spine surgeons, these can range from $50,000 to over $200,000.

- Call Pay: Surgeons are often paid a stipend for being on-call for the hospital emergency department. This can be a per diem rate or an hourly rate for time spent managing emergent cases.

- Profit Sharing / Partnership Income (Private Practice): For surgeons who are partners in a private practice, a significant portion of their income comes from the group's net profits. This can include revenue from surgery, clinic visits, imaging (if the practice owns an MRI or X-ray machine), and physical therapy centers. This model offers the highest earning potential but also carries the risks and responsibilities of business ownership.

- Other Benefits and Perks:

- Retirement Plans: Robust 401(k) or 403(b) plans with generous employer matching contributions.

- Health and Disability Insurance: Comprehensive coverage is standard.

- Malpractice Insurance: Paid for by the employer, often with "tail coverage" included, which is crucial.

- Continuing Medical Education (CME) Allowance: An annual stipend (e.g., $5,000 - $15,000) to cover the cost of attending conferences and staying current with medical advances.

- Relocation Assistance: A one-time payment to help with the cost of moving for a new job.

---

Key Factors That Influence Salary

While the national average provides a useful benchmark, an individual orthopedic spine surgeon's salary is determined by a complex interplay of variables. Understanding these factors is crucial for anyone planning a career in this field, as strategic decisions made early on can have a profound impact on long-term earning potential.

###

Level of Education and Sub-Specialization

In medicine, education is the foundation of earning power, and for a spine surgeon, the path is exceptionally long. The baseline requirement is a Doctor of Medicine (M.D.) or Doctor of Osteopathic Medicine (D.O.) degree, followed by a demanding five-year orthopedic surgery residency. However, it is the subsequent, highly competitive one-year spine surgery fellowship that truly unlocks the highest salary potential.

- The Fellowship Premium: A general orthopedic surgeon is not qualified to perform most complex spinal procedures. The fellowship provides intensive, specialized training in the diagnosis and surgical management of all aspects of the spine. This additional year of training is non-negotiable for this career path and is the primary differentiator that elevates a spine surgeon's salary far above that of a generalist or even other orthopedic subspecialists like hand or foot and ankle surgeons.

- Fellowship Prestige: The reputation of the fellowship program can also play a role. Graduating from a world-renowned spine program (e.g., at institutions like the Hospital for Special Surgery, Rush University, or the Mayo Clinic) can open doors to more prestigious academic positions or high-paying private practice opportunities.

- Further Sub-specialization: Within the field of spine surgery, there are even more niche areas that can impact earnings. For example, surgeons who specialize in complex pediatric deformity (scoliosis) or adult deformity correction often command higher salaries due to the extreme complexity, length, and high reimbursement rates of these procedures. Specialization in minimally invasive spine surgery (MISS) is also a highly valued and marketable skill.

###

Years of Experience and Reputation

As with most professions, experience is a primary driver of salary growth, but in surgery, its effect is exponential.

- The Learning Curve (Years 0-3): As detailed in the salary bracket table, the first few years post-fellowship are about building a practice. Surgeons are honing their skills, building speed and efficiency in the operating room, and establishing a referral network with primary care physicians, physiatrists, and chiropractors in the community. Salaries are often guaranteed during this period to provide stability.

- Peak Earning Years (Years 4-20): This is where compensation shifts almost entirely to a productivity model (RVUs). A mid-career surgeon has a well-established reputation. They are known for good outcomes, which leads to a steady stream of patient referrals. Their surgical skills are highly refined, allowing them to perform surgeries more efficiently and handle a higher volume of complex cases. A surgeon who can perform four successful surgeries in a day will earn significantly more than one who can only do two. This efficiency is the engine of high seven-figure incomes.

- Late Career and Leadership (Years 20+): While surgical volume may begin to plateau or slightly decrease, senior surgeons often supplement their income through other avenues. They may become the managing partner of their private practice, the Chief of Orthopedic Surgery at a hospital, or a fellowship director. They are also sought after for lucrative consulting work with medical device companies or as expert witnesses in legal cases, which can pay thousands of dollars per hour.

###

Geographic Location

Where a spine surgeon chooses to practice is one of the most significant factors influencing their salary. The dynamic is often counterintuitive: salaries are frequently higher in less traditionally "desirable" locations due to the basic principles of supply and demand.

- High-Paying Regions: According to data from physician recruiting firms and compensation reports like those from the Medical Group Management Association (MGMA), the highest salaries are often found in the Midwest, Southeast, and non-coastal West. States like Wyoming, Alabama, Indiana, and Oklahoma often offer top-tier compensation to attract and retain highly specialized talent that is in short supply. A hospital in a mid-sized Midwestern city might offer a starting package of $800,000+ to entice a spine fellow who might otherwise be drawn to a major coastal city.

- Lower-Paying Regions: Major metropolitan areas on the coasts—such as New York City, Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Boston—tend to have lower average salaries. This is because there is a large supply of surgeons who want to live and work in these areas for lifestyle reasons. The high concentration of academic medical centers also contributes, as these institutions traditionally pay less than private practice.

- Rural vs. Urban: Rural areas often pay a premium. A "lone wolf" spine surgeon serving a large, underserved rural catchment area can be extremely busy and highly compensated, as they face little to no competition.

Example Salary Variation by State (Illustrative Data)

| State/Region | Typical Compensation Range | Rationale |

| :--- | :--- | :--- |

| Wyoming/North Dakota | $900,000 - $1,500,000+ | High demand, very low supply of specialists. |

| Alabama/Mississippi | $850,000 - $1,300,000 | Strong demand in the Southeast, need to offer competitive salaries to recruit. |

| Wisconsin/Indiana | $800,000 - $1,200,000 | Robust healthcare systems in the Midwest competing for limited talent. |

| California (Major Metro) | $600,000 - $950,000 | High desirability, large supply of surgeons, higher cost of living offsets some salary gains. |

| New York (NYC) | $550,000 - $900,000 | Saturated market, dominated by academic centers with lower pay scales. |

###

Practice Setting (Company Type)

The type of organization a surgeon works for profoundly shapes their compensation structure, work-life balance, and overall career trajectory.

- Physician-Owned Private Practice: This setting traditionally offers the highest earning potential. Surgeons are either partners or on a partnership track. Income is directly tied to the practice's overall profitability. In addition to their own surgical productivity, partners share in the profits from ancillary services like physical therapy, imaging (MRI/X-ray), and ambulatory surgery centers (ASCs). However, this comes with the responsibilities of a business owner: managing staff, marketing, billing, and covering overhead costs.

- Hospital or Health System Employment: This is an increasingly common model. The hospital employs the surgeon directly, providing a stable, often guaranteed salary plus a productivity bonus. The hospital handles all administrative and business aspects, allowing the surgeon to focus solely on clinical medicine. While the absolute ceiling on income is typically lower than in private practice (as the hospital keeps a larger portion of the revenue generated), it offers greater security, better benefits, and less personal financial risk.

- Academic Medical Centers: Surgeons at university-affiliated hospitals typically earn the least in terms of direct cash compensation. A significant portion of their time is dedicated to non-revenue-generating activities like teaching residents and fellows, conducting research, and publishing papers. The "payment" comes in the form of prestige, intellectual stimulation, access to cutting-edge technology, and the opportunity to shape the future of medicine.

- Locum Tenens: This involves working as a temporary, independent contractor to fill in for other surgeons who are on vacation, leave, or to cover staffing shortages. *Locum tenens* spine surgeons can command extremely high daily or weekly rates (e.g., $3,000 - $5,000+ per day), but these positions do not include benefits, retirement contributions, or paid time off, and the work can be inconsistent.

###

In-Demand Skills and Procedural Expertise

Beyond the basic fellowship training, developing a reputation for expertise in specific, high-value areas can significantly boost a surgeon's marketability and income.

- Minimally Invasive Spine Surgery (MISS): Techniques that use smaller incisions, specialized tools, and endoscopic visualization are in high demand. MISS procedures often lead to less pain, shorter hospital stays, and faster recovery times for patients, making them highly attractive. Surgeons proficient in MISS are sought after by hospitals and patients alike.

- Robotic-Assisted Surgery: Proficiency with surgical robotic systems (like Mazor X or Globus ExcelsiusGPS) is a cutting-edge skill. These systems enhance precision, particularly in screw placement, and hospitals with this technology need surgeons trained to use it. This skill can be a major negotiating point for a higher salary.

- Complex Deformity Correction: As mentioned earlier, adult and pediatric deformity surgery (for conditions like severe scoliosis) is among the most challenging and highest-reimbursing work a spine surgeon can do. These are long, arduous operations that only a subset of spine surgeons are comfortable and qualified to perform, creating high demand for their expertise.

- Anterior Spine Access: Many spinal procedures, particularly in the neck (ACDF) and lower back (ALIF), require an anterior approach (from the front). Some spine surgeons partner with a vascular or general surgeon for this access, while others are trained to do it themselves. The ability to perform one's own anterior access can increase efficiency and revenue.

- Business Acumen: For those in private practice, skills in management, finance, and marketing are invaluable. A surgeon who understands how to run a lean, efficient practice and effectively market their services will earn substantially more than a peer who is a great clinician but a poor businessperson.

---

Job Outlook and Career Growth

The long-term career outlook for orthopedic spine surgeons is exceptionally strong, driven by a convergence of demographic, technological, and lifestyle trends. While the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) provides general data for physicians and surgeons, the specifics for this subspecialty are even more robust.

The BLS projects a 3% growth for all physicians and surgeons from 2022 to 2032, which is about average. However, this general number masks the powerful demand within specific high-need specialties. For orthopedic surgery, and particularly spine surgery, the outlook is significantly brighter for several key reasons:

1. The Aging Population: The primary driver of demand is the aging of the Baby Boomer generation. As people live longer, the incidence of age-related degenerative spinal conditions—such as spinal stenosis, degenerative disc disease, and spondylolisthesis—is increasing dramatically. This demographic shift creates a large and growing patient population in need of both non-operative and surgical spine care.

2. Active Lifestyles and Sports Injuries: Unlike previous generations, today's older adults often remain physically active, leading to more sports-related and overuse injuries of the spine. Furthermore, younger populations are heavily involved in high-impact sports, contributing to a steady stream of patients with traumatic spinal injuries, disc herniations, and fractures.

3. Technological and Procedural Advances: The development of less invasive surgical techniques, better implant materials, and robotic-assisted navigation has made surgery a safer and more viable option for a broader range of patients. Conditions that were once considered unmanageable or too risky to operate on can now be treated effectively, expanding the pool of surgical candidates.

4. Limited Supply of Specialists: The pipeline for creating new spine surgeons is long and narrow. The number of orthopedic surgery residency spots is limited, and the number of spine surgery fellowship positions is even smaller. This restricted supply, coupled with soaring demand, ensures that qualified spine surgeons will remain a highly sought-after and well-compensated commodity for the foreseeable future.

### Emerging Trends and Future Challenges

The field of spine surgery is not static. Surgeons entering the field today must be prepared to adapt to a rapidly evolving landscape.

Key Trends:

- Shift to Ambulatory Surgery Centers (ASCs): Increasingly, less complex procedures like single-level fusions and laminectomies are moving from the inpatient hospital setting to outpatient ASCs. This trend is driven by lower costs, greater efficiency, and high patient satisfaction. Surgeons who are partners in or can operate at ASCs may see increased income potential.

- Biologics and Regenerative Medicine: Research into stem cells, platelet-rich plasma (PRP), and other biologics to promote bone healing and potentially even regenerate disc tissue is a major frontier. While still largely experimental for many applications, these technologies could one day revolutionize non-operative spine care and supplement surgical fusions.

- AI and Data Analytics: Artificial intelligence is beginning to play a role in pre-operative planning, using large datasets to predict surgical outcomes and identify at-risk patients. AI can help surgeons select the optimal approach and implant size for a given patient's unique anatomy.

- Value-Based Care Models: The healthcare system is slowly shifting from a fee-for-service model (where payment is based on volume) to a value-based model (where payment is tied to patient outcomes and cost-effectiveness). Surgeons will increasingly need to demonstrate not just that they can perform a surgery, but that the surgery leads to measurable improvements in a patient's function and quality of life in a cost-effective manner.

Future Challenges:

- Reimbursement Pressure: Insurance companies and government payers like Medicare are constantly seeking to control costs. This can lead to downward pressure on reimbursement rates for spinal procedures, which could temper future salary growth if not offset by increased efficiency or volume.

- Burnout: The demands of being a spine surgeon are immense. The long hours, high-pressure operating room environment, administrative burdens, and the emotional weight of dealing with patients in severe pain can lead