For countless aspiring dancers, the dream is painted in satin and tulle, set to the soaring notes of Tchaikovsky. It’s the hushed anticipation of a packed theatre, the warmth of the spotlight, and the transcendent moment of a weightless leap across the stage. This dream, the life of a professional ballerina, is one of unparalleled dedication, physical discipline, and artistic expression. But beyond the proscenium arch, away from the applause, lies the practical reality of making a living. The query "professional ballerina salary" is more than just a search for a number; it's a question about viability, sustainability, and whether a life devoted to this demanding art form can also be a life of financial stability.

The answer is complex, nuanced, and far from a single figure. A professional ballerina's salary can range from a modest stipend that barely covers living expenses to a six-figure income reserved for the superstars of the world's most prestigious companies. The journey is not a straightforward corporate ladder but a challenging ascent where talent, tenacity, and the right opportunities converge. Having spent years analyzing career paths across every industry, I once interviewed a principal dancer who described her career not as a job, but as a calling that demanded her entire being, physically and emotionally, for a contract that lasted only 40 weeks a year. This sentiment perfectly captures the unique financial and personal landscape of a professional dancer, a reality this guide is designed to illuminate.

This comprehensive article will serve as your ultimate resource, demystifying the financial aspects of a ballet career. We will dissect salary data from authoritative sources, explore the critical factors that dictate earnings, and map out the path from the first plié in a local studio to securing a contract with a professional company.

### Table of Contents

- [What Does a Professional Ballerina Do?](#what-does-a-professional-ballerina-do)

- [Average Professional Ballerina Salary: A Deep Dive](#average-professional-ballerina-salary-a-deep-dive)

- [Key Factors That Influence a Ballerina's Salary](#key-factors-that-influence-a-ballerinas-salary)

- [Job Outlook and Career Growth for Professional Ballerinas](#job-outlook-and-career-growth-for-professional-ballerinas)

- [How to Become a Professional Ballerina: A Step-by-Step Guide](#how-to-become-a-professional-ballerina-a-step-by-step-guide)

- [Conclusion: Is a Career in Ballet Right for You?](#conclusion-is-a-career-in-ballet-right-for-you)

What Does a Professional Ballerina Do?

The role of a professional ballerina extends far beyond the two or three hours of a performance. The grace and effortlessness seen on stage are the culmination of a grueling, continuous cycle of training, rehearsal, and physical maintenance. A ballerina is, at her core, an elite athlete and a performing artist, responsible for interpreting choreography, embodying a character, and executing physically demanding movements with precision and artistry.

Their work is grounded in the structure of a ballet company. Most professional dancers are not freelancers; they are employees of a specific company for a contracted season, which can range from 25 to over 40 weeks per year. Their responsibilities are multifaceted and governed by a rigorous schedule.

Core Responsibilities and Daily Tasks:

- Daily Company Class: The workday for every dancer, from the newest apprentice to the most celebrated principal, begins with a mandatory 90-minute ballet technique class. This serves as a warm-up, a continuous refinement of fundamental skills, and a way for the artistic staff to assess the dancers.

- Rehearsals: The bulk of a ballerina's day—often six to eight hours—is spent in the rehearsal studio. This involves learning new choreography for upcoming ballets, rehearsing existing repertoire for upcoming performances, and receiving corrections and coaching from ballet masters, choreographers, and artistic directors. This process is both physically and mentally exhaustive, requiring intense focus and the ability to quickly absorb and apply complex movement sequences.

- Performance: During performance weeks, the schedule shifts. Days are still filled with class and rehearsals, but the evening is dedicated to the show. This involves pre-performance rituals, extensive makeup and hair preparation, costume fittings, and warming up, followed by the performance itself. After the show, a proper cool-down is essential to prevent injury.

- Physical Conditioning and Maintenance: A ballerina's body is her instrument, and maintaining it in peak condition is a non-negotiable part of the job. This includes cross-training (such as Pilates, Gyrotonic, or swimming), strength and conditioning workouts, and regular appointments with physical therapists, massage therapists, and other specialists to manage and prevent injuries.

- Costume Fittings and Shoe Preparation: Dancers spend considerable time in fittings to ensure their costumes are perfectly tailored for both aesthetic and movement. A significant, often daily, task is the preparation of pointe shoes—sewing ribbons and elastics, breaking them in, and applying products like shellac to harden them for optimal performance. A single principal dancer can go through over 100 pairs of pointe shoes in a season.

### A Day in the Life of a Corps de Ballet Dancer (Rehearsal Day)

To make this tangible, let's walk through a typical non-performance day for a ballerina in a large, unionized company.

- 9:00 AM - 9:30 AM: Arrive at the theatre/studio. Personal warm-up, stretching, and preparing pointe shoes for the day.

- 9:30 AM - 11:00 AM: Mandatory company-wide technique class on stage or in the largest studio.

- 11:15 AM - 1:30 PM: Rehearsal Block 1. Working on a full-length classical ballet, such as *Giselle*, focusing on formations and unison work for the *corps de ballet*.

- 1:30 PM - 2:30 PM: Lunch Break. This hour is often shared with a physical therapy appointment or a quick session with a trainer.

- 2:30 PM - 4:00 PM: Rehearsal Block 2. Rehearsing a different piece, perhaps a contemporary work by a guest choreographer, which demands a different style of movement and mindset.

- 4:15 PM - 6:00 PM: Rehearsal Block 3. Potentially a "notes" session for a ballet premiering soon, or a run-through of a section of *The Nutcracker* if it's that time of year.

- 6:00 PM onwards: End of the official workday. The evening may involve a personal workout, a Pilates session, meal prepping for the next day, or simply heading home for rest and recovery—the most critical part of an athlete's training.

This schedule illustrates that being a ballerina is a full-time, all-encompassing profession where discipline, resilience, and an unyielding passion for the art form are the true prerequisites for success.

Average Professional Ballerina Salary: A Deep Dive

Analyzing the salary of a professional ballerina requires looking beyond a single national average. The compensation structure in the ballet world is highly stratified and directly linked to the prestige of the company, the dancer's rank, and union representation.

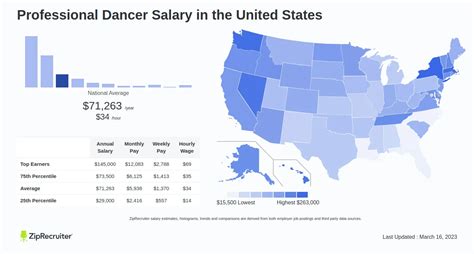

The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) groups dancers and choreographers together under the SOC code 27-2032. As of May 2023, the BLS reports the following national figures for this category:

- Median Hourly Wage: $23.83

- Median Annual Salary: $49,560

- Salary Range: The lowest 10 percent earned less than $17.06 per hour ($35,480 annually), while the top 10 percent earned more than $57.97 per hour ($120,580 annually).

Source: *U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Occupational Outlook Handbook, Dancers and Choreographers (Data from May 2023).*

While this data provides a general benchmark, it's crucial to understand that it aggregates all forms of professional dance (Broadway, modern, commercial, cruise ships) and choreography. The salary for a classical ballerina within a company structure has its own unique norms.

The life of a company dancer is governed by a contract, typically for a "season" of 30-42 weeks. This means their annual salary is their weekly pay multiplied by the number of weeks in their contract. This is a critical distinction from a standard 52-week salaried job.

Salary aggregators provide further insight, though they also often blend different dance styles:

- Salary.com reports the average dancer salary in the United States is around $54,301 as of May 2024, with a typical range falling between $44,501 and $66,601.

- Payscale.com indicates an average base salary of $51,000 per year for dancers, but data is limited and user-submitted.

The most accurate way to understand ballerina salaries is to break them down by rank and company tier, as these are the most significant determining factors.

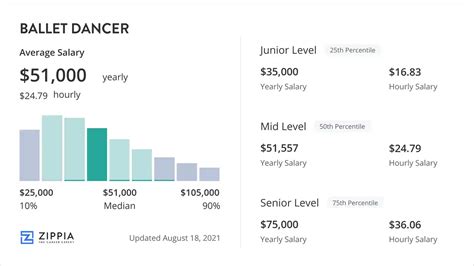

### Ballerina Salary by Rank and Experience Level

Within a ballet company, a dancer's salary is directly tied to their position in the hierarchy. These ranks are earned through years of exceptional performance, technical skill, and artistic merit.

| Career Stage / Rank | Typical Experience | Average Weekly Salary Range (Union Co.) | Estimated Annual Salary Range (38-Week Contract) | Description |

| :--- | :--- | :--- | :--- | :--- |

| Apprentice/Trainee | 0-2 years | $600 - $1,100 | $22,800 - $41,800 | A transitional role between student and full company member. Paid a stipend, often below union minimums. |

| Corps de Ballet | 2-8 years | $1,200 - $2,500 | $45,600 - $95,000 | The main body of the company. The "entry-level" full-time position. Salary is set by union scale based on years of service. |

| Soloist | 5-15 years | $2,000 - $3,500 | $76,000 - $133,000 | A featured dancer who performs solo roles. Salary is above the corps scale and may be individually negotiated. |

| Principal Dancer | 10+ years | $3,000 - $6,000+ | $114,000 - $228,000+ | The star of the company. These salaries are often highly negotiated and can significantly exceed union minimums. |

*Note: These figures are estimates based on publicly available data and industry knowledge of companies unionized with the American Guild of Musical Artists (AGMA). Non-union and smaller regional companies may pay significantly less.*

### Deconstructing the Compensation Package

A ballerina's income is more than just the weekly paycheck. A comprehensive compensation package, especially in a union company, includes several vital components:

- Weekly Salary: The core of a dancer's pay, received only during the contracted weeks of the season (the "work weeks").

- Pointe Shoe Allowance: Most professional companies provide an allowance for or direct supply of pointe shoes. Given that a principal can use a pair per performance, this is a significant benefit worth thousands of dollars per year. A single pair of professional-quality pointe shoes costs $100-$150.

- Health Insurance: Union contracts (and most reputable companies) provide comprehensive health, dental, and vision insurance, which is critical in such a physically demanding profession.

- Retirement Plans: Many larger companies offer 401(k) or similar retirement plans, often with a company match. AGMA also has a pension plan.

- Touring Per Diem: When the company travels, dancers receive a per diem—a daily allowance to cover the cost of meals and incidentals. This tax-free stipend can range from $75 to $150 per day, providing a supplemental income stream during tours.

- Performance Bonuses: While not standard for the corps, soloists and principals may have performance bonuses for specific roles or a set number of shows written into their contracts.

- Layoff Pay / Unemployment: During the "off-season" (the weeks not covered by the contract), dancers are laid off. They are eligible to collect unemployment benefits, which is a planned and essential part of their annual income strategy. Many also supplement this time with teaching or guest performances.

Understanding this structure reveals that a ballerina's financial life is one of careful planning, managing a seasonal income to last the full year. The headline salary figure only tells part of the story.

Key Factors That Influence a Ballerina's Salary

The vast range in a professional ballerina's salary is not arbitrary. It's dictated by a clear set of hierarchical and economic factors. For an aspiring dancer, understanding these variables is crucial for setting realistic career expectations and making strategic decisions. Here, we delve into the most impactful elements that determine a dancer's paycheck.

### 1. Company Tier and Budget

This is, without question, the single most significant factor influencing a ballerina's salary. Ballet companies in the United States exist in a distinct hierarchy, largely defined by their annual operating budget, location, performance season length, and union status.

- Top-Tier International Companies (e.g., New York City Ballet, American Ballet Theatre): These are the giants of the ballet world, with annual budgets often exceeding $50 million. They are based in major cultural hubs, have the longest performance seasons (often 40+ weeks), and offer the highest salaries in the industry. Their dancers are represented by the American Guild of Musical Artists (AGMA), which negotiates strong collective bargaining agreements that set minimum salaries for each rank, overtime pay, and excellent benefits. A senior corps de ballet dancer at one of these companies can easily earn over $100,000 annually before any overtime or special considerations. Principals at this level can command salaries well into the high six figures.

- Major Regional Companies (e.g., San Francisco Ballet, Boston Ballet, Houston Ballet, Pacific Northwest Ballet): These are prestigious, internationally recognized companies with substantial budgets (typically $15 million to $40 million). They are also AGMA-affiliated and offer competitive salaries and benefits, though often slightly below the top New York companies. Their contract seasons are also robust, usually ranging from 35 to 40 weeks. Dancers in these companies enjoy a high standard of living and significant artistic opportunities.

- Mid-Sized and Smaller Regional Companies: This category includes a wide array of companies across the country. Many are unionized with AGMA, but their smaller budgets mean their union-negotiated salary scales are lower. Their seasons are often shorter (28-34 weeks), which directly impacts annual income. The difference in weekly pay might be a few hundred dollars, but a 10-week shorter season can mean a $15,000-$20,000 difference in yearly earnings.

- Non-Union, "Project-Based," or Pre-Professional Companies: At the lower end of the pay scale are smaller, non-union companies. They often operate on shoestring budgets, offer very short contracts (sometimes on a per-performance or project basis), and pay far less. It's not uncommon for dancers in these companies to earn an annual salary below the poverty line and need to supplement their income with multiple other jobs. Many young dancers start in these environments to gain experience, but it is not a financially sustainable long-term career path.

### 2. Rank Within the Company

As detailed in the salary table above, rank is the primary internal factor. The progression from Apprentice to Corps de Ballet, then to Soloist, and finally to Principal is the main path to a higher salary within a single company.

- Apprentice: Essentially a paid internship. The pay is a stipend meant to cover basic living costs while the dancer proves their worth.

- Corps de Ballet: The backbone of the company. In union companies, their salary increases incrementally each year based on seniority, as stipulated in the collective bargaining agreement.

- Soloist: A significant pay jump from the corps. They are guaranteed featured roles and their salary reflects this added responsibility and artistic pressure.

- Principal: The pinnacle of the career. Principals are the face of the company, and their salaries are often individually negotiated, going far beyond the standard union scale. Their compensation reflects their star power, marketability, and the audience they can draw.

### 3. Union Representation (AGMA)

The importance of the American Guild of Musical Artists (AGMA) cannot be overstated. For dancers in the United States, being a member of an AGMA company is the most critical element for ensuring fair wages, safe working conditions, and benefits.

- Minimum Salaries: AGMA negotiates a "basic agreement" with each company that stipulates the minimum weekly salary for every rank, including yearly increases. This prevents companies from underpaying dancers.

- Working Hours and Overtime: AGMA contracts strictly regulate the number of hours a dancer can rehearse per day and per week. Any work beyond these hours (e.g., for special events, extra rehearsals, or media calls) must be paid as overtime, often at 1.5x or 2x the dancer's prorated hourly rate. This can add a significant amount to a dancer's income, especially during busy performance seasons.

- Health and Safety: The union ensures safe working conditions, from the quality of the dance floors to rules about partnering and breaks to prevent injury. They also negotiate for comprehensive health insurance and disability coverage.

- Job Security: AGMA contracts provide grievance procedures and rules for dismissal, offering a layer of job security that does not exist in non-union companies.

A dancer in a non-union company has none of these protections and must negotiate every aspect of their contract individually, with far less leverage. This almost invariably leads to lower pay, longer hours, and fewer benefits.

### 4. Geographic Location and Cost of Living

Location's impact is intrinsically tied to the company's tier. The highest-paying companies are located in the most expensive cities, such as New York City and San Francisco.

- High-Paying, High Cost-of-Living Cities: New York, NY; San Francisco, CA; Boston, MA; Washington, D.C.; Chicago, IL. According to BLS data, New York and California are among the top-paying states for dancers. While a salary of $90,000 in New York is substantial, the purchasing power may be equivalent to a lower salary in a city with a cheaper cost of living.

- Competitive Pay, Moderate Cost-of-Living Cities: Houston, TX; Seattle, WA; Philadelphia, PA. Companies in these cities (like Houston Ballet or Pacific Northwest Ballet) offer strong salaries that can provide an excellent quality of life due to the lower cost of housing and daily expenses.

- Lower Pay, Lower Cost-of-Living Areas: Smaller regional companies in the Midwest or South may offer salaries that seem low on a national scale, but may be more manageable within the local economy.

Aspiring dancers must weigh a higher nominal salary against the cost of living in that city to understand their true earning potential.

### 5. Training, Pedigree, and "Star Power"

Unlike corporate jobs where a degree (B.S. vs. M.S.) dictates salary, in ballet, it's about training pedigree. Attending a world-renowned school affiliated with a major company (e.g., the School of American Ballet for NYCB, or the Vaganova Academy in Russia) can provide a direct pipeline to a top-tier career and higher starting potential.

Furthermore, for principal dancers, individual "star power" becomes a major negotiating tool. A dancer with a large social media following, mainstream recognition (like Misty Copeland), or a history of winning major international competitions (like the Prix de Lausanne) has immense market value. They can secure lucrative guesting contracts with other companies during their off-season and sign endorsement deals with dancewear brands, athletic companies (like Under Armour or Nike), and even luxury brands. These outside activities can sometimes eclipse their company salary, but this level of earning is reserved for a very small, elite group of dancers at the absolute peak of the profession.

Job Outlook and Career Growth for Professional Ballerinas

The path of a professional ballerina is one of intense highs and significant challenges. While the artistic rewards are profound, the career is characterized by fierce competition, a limited number of positions, and a finite performance lifespan. Understanding the long-term outlook is essential for anyone committing their life to this art.

### Job Outlook Projections

The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) provides a sobering but realistic picture of the field. For the "Dancers and Choreographers" category, the BLS projects job growth of just 2 percent from 2022 to 2032. This is slower than the average for all occupations.

The BLS states, "About 2,700 openings for dancers and choreographers are projected each year, on average, over the decade. Many of those openings are expected to result from the need to replace workers who transfer to different occupations or exit the labor force, such as to retire."

Key Takeaways from the BLS Outlook:

1. Extreme Competition: The number of talented dancers graduating from pre-professional programs far exceeds the number of available positions in professional companies. Auditions for major companies can attract hundreds of highly qualified dancers for only one or two open spots.

2. Reliance on Funding: The health of the ballet world is directly tied to the economy. Professional dance companies are primarily non-profit organizations that rely on ticket sales, private donations, and grants. During economic downturns, funding for the arts can be a low priority, leading to shorter seasons, hiring freezes, or even the closure of companies.

3. Short Career Span: This is perhaps the most defining characteristic of the profession. Most ballerinas retire from performing in their mid-to-late 30s or early 40s due to the cumulative physical toll. This means that they must plan for a "second career" from a very early stage.

### Future Challenges and Emerging Trends

The world of ballet is not static. Dancers today face a different landscape than those of previous generations, with unique challenges and new opportunities.

Challenges:

- Physical Toll and Injury: The push for more athletic, complex, and daring choreography has increased the physical demands and risk of career-ending injuries.

- Mental Health: Awareness is growing around the immense psychological pressure dancers face concerning body image, competition, perfectionism, and career uncertainty.

- Financial Instability: The seasonal nature of contracts and the need to supplement income during layoffs remain a constant financial stressor for many dancers outside the top-tier companies.

Emerging Trends and Opportunities:

- Versatility is Key: Companies are increasingly programming mixed repertoires that include classical, neoclassical, and contemporary works. Dancers who are versatile and can excel in multiple styles are more valuable and marketable.

- The Rise of the "Dancerpreneur": Social media has empowered dancers to build personal brands. A strong online presence can lead to endorsement deals, teaching opportunities, and a platform to launch their own projects, creating income streams independent of a company contract.

- Focus on Health and Wellness: Companies are investing more in dancer health, with on-site physical therapists, nutritionists, and mental health professionals becoming more common. This focus on wellness can potentially extend career longevity.

- Digital and Virtual Performance: The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the adoption of digital seasons and virtual performances. While not a replacement for live theatre, this has created new avenues for reaching global audiences and generating revenue.

### Career Advancement and Post-Performance Pathways

Advancement within a performing career means ascending the company ranks from corps de ballet to principal. This requires not only exceptional talent and work ethic but also catching the eye of the artistic director and being given opportunities to perform featured roles.

However, the most crucial aspect of career growth for a ballerina is planning for life after the stage. The discipline, resilience, and body awareness gained from a ballet career are highly transferable skills. Common "second careers" include:

- Artistic Leadership: Becoming a Ballet Master/Mistress (responsible for rehearsing the company), a Choreographer, or an Artistic Director of a company.

- Teaching: A highly popular path. Dancers may teach at professional company schools, private studios, or universities. Many go on to open their own successful ballet schools.

- Arts Administration: Working behind the scenes in development, fundraising, marketing, or management for a ballet company or other arts organization.

- Bodywork and Somatics: Many former dancers become certified instructors in Pilates, Gyrotonic, or yoga. Others pursue degrees in physical therapy, using their intimate knowledge of the body to help other dancers.

- **Higher Education