For those captivated by the echoes of the past—the rise and fall of empires, the clash of ideologies, and the stories of human struggle and triumph—a career as a history professor can seem like the ultimate calling. It’s a path that promises a life of the mind, one spent unearthing forgotten narratives, shaping the understanding of new generations, and contributing to the grand, ongoing conversation about who we are and how we got here. But passion, while essential, must be paired with practicality. Aspiring academics and curious students alike inevitably ask the critical question: What does a professor history salary actually look like?

This guide is designed to be your definitive resource, moving beyond simple averages to provide a granular, in-depth analysis of a history professor's earnings, career trajectory, and the complex realities of the academic job market. We will dissect the key factors that determine your salary, from the type of institution you work for to your geographic location and scholarly reputation. The average history professor in the United States earns a salary that typically falls between $70,000 and $130,000 per year, but this figure is just the beginning of the story. I once sat in on a history lecture where the professor made the fall of the Roman Empire feel as immediate and urgent as today's headlines. It was a masterclass not just in history but in storytelling, and it underscored the profound intellectual and personal rewards of a career dedicated to illuminating the past.

This article will provide you with the data-driven insights and expert advice needed to navigate this challenging yet deeply fulfilling profession. We will explore not only how much you can earn but also what the job truly entails, what the future holds for the discipline, and a step-by-step roadmap to get you started.

### Table of Contents

- [What Does a History Professor Do?](#what-does-a-history-professor-do)

- [Average Professor History Salary: A Deep Dive](#average-professor-history-salary-a-deep-dive)

- [Key Factors That Influence Salary](#key-factors-that-influence-salary)

- [Job Outlook and Career Growth](#job-outlook-and-career-growth)

- [How to Get Started in This Career](#how-to-get-started-in-this-career)

- [Conclusion](#conclusion)

What Does a History Professor Do?

The title "history professor" often conjures an image of a charismatic figure standing before a crowded lecture hall, weaving compelling narratives about ancient battles or political revolutions. While teaching is a central and highly visible part of the job, it represents only one facet of a multifaceted and demanding career. The professional life of a university professor, particularly in a field like history, is traditionally built upon three core pillars: Teaching, Research, and Service.

1. Teaching:

This is the most public-facing aspect of the role. A history professor's teaching duties extend far beyond delivering lectures. They are responsible for:

- Developing Curricula: Designing entire courses from the ground up, including creating a detailed syllabus, selecting readings, and structuring assignments and exams.

- Leading Instruction: Delivering engaging lectures, facilitating seminar discussions where students critically analyze primary and secondary sources, and guiding student-led presentations.

- Mentoring and Advising: Holding regular office hours to provide one-on-one guidance, advising students on their academic paths, writing letters of recommendation, and supervising undergraduate honors theses or graduate dissertations.

- Grading and Assessment: Providing thoughtful, constructive feedback on a wide range of student work, from short essays and research papers to comprehensive final exams.

2. Research and Scholarship:

For most tenure-track professors, particularly at research-focused universities, being an active scholar is a non-negotiable requirement. This is the work that pushes the boundaries of historical knowledge. It involves:

- Conducting Original Research: Spending countless hours in archives, libraries, and special collections around the world, poring over original documents, manuscripts, and artifacts.

- Writing and Publishing: Transforming research findings into scholarly articles for peer-reviewed journals and, most importantly for tenure, writing and publishing books with reputable academic presses. This is a multi-year endeavor that establishes their expertise.

- Presenting at Conferences: Sharing research findings with peers at national and international academic conferences, a key venue for receiving feedback and building a professional network.

- Applying for Grants: Writing detailed proposals to secure funding from organizations like the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) or private foundations to support research travel and writing time.

3. Service:

The "service" component is the glue that holds the academic community together. Professors are citizens of their university and are expected to contribute to its governance and intellectual life. Service includes:

- Departmental Duties: Attending faculty meetings, serving on hiring committees for new professors, participating in curriculum reviews, and helping to organize departmental events.

- University-Wide Committees: Serving on committees related to admissions, faculty governance, student conduct, or library acquisitions.

- Professional Service: Contributing to the broader historical profession by peer-reviewing manuscripts for academic journals and presses, or holding leadership roles in professional organizations like the American Historical Association (AHA).

### A Day in the Life of a Tenured History Professor

To make this tangible, let's imagine a typical Tuesday for Dr. Eleanor Vance, a tenured Associate Professor of 19th-Century American History at a state university:

- 8:00 AM - 9:00 AM: Arrive on campus. Respond to student emails and review lecture notes for the day.

- 9:30 AM - 10:45 AM: Teach "HIS 101: The U.S. to 1877." This is a large survey course with 120 students. The lecture today is on the causes of the Civil War.

- 11:00 AM - 1:00 PM: Office Hours. Three undergraduate students stop by: one to discuss a paper topic, another struggling with the readings, and a third to ask for a letter of recommendation for law school.

- 1:00 PM - 2:00 PM: Lunch while reading a new article in the *Journal of American History* to stay current in the field.

- 2:00 PM - 3:30 PM: Departmental Faculty Meeting. The agenda includes discussing the search for a new professor in East Asian history and debating changes to the major requirements.

- 3:30 PM - 5:30 PM: Protected "Research Time." Dr. Vance heads to the library's special collections to work with a collection of letters from a Civil War soldier, which forms the basis for her next book project.

- 5:30 PM - 7:00 PM: Head home. After dinner, she spends an hour reading and providing feedback on a chapter from one of her PhD student's dissertations.

This schedule illustrates the constant balancing act between teaching, research, and administrative duties that defines the life of a history professor.

Average Professor History Salary: A Deep Dive

Determining a precise salary for a history professor requires looking at multiple data sources, as compensation varies significantly based on rank, institution type, and location. While the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) is the gold standard for employment data, it groups all "Postsecondary Teachers" together, which can obscure the nuances of a specific field like history. However, it provides a crucial baseline.

According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics' May 2023 Occupational Employment and Wage Statistics, the median annual wage for all Postsecondary Teachers was $84,380. The lowest 10 percent earned less than $41,920, and the highest 10 percent earned more than $183,970. This wide range highlights the immense variability in academic salaries.

To get more specific to the field of history, we must turn to salary aggregators and professional surveys, which provide data based on job titles.

National Average and Typical Salary Range

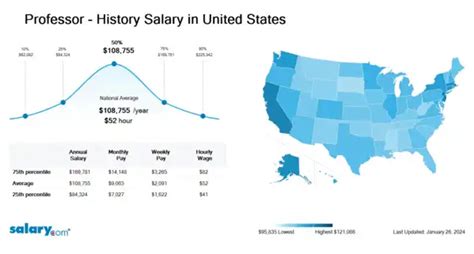

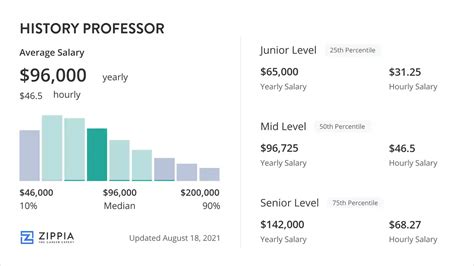

Data from several reputable sources paint a more detailed picture for "History Professor":

- Salary.com (as of late 2023) reports that the average History Professor salary in the United States is $105,735, with a typical salary range falling between $83,088 and $176,511.

- Glassdoor (as of 2024) estimates the total pay for a History Professor in the U.S. to be around $114,000 per year, with a likely range between $86,000 and $153,000.

- Payscale.com (as of 2024) provides a slightly more modest figure, with an average salary of $74,950, but this figure likely includes a higher proportion of data from non-tenure track and adjunct faculty.

Key takeaway: A reasonable expectation for a full-time, tenure-track history professor's salary falls somewhere between $75,000 and $125,000, with significant potential for higher earnings based on the factors we'll explore below.

### Salary Brackets by Academic Rank and Experience

The most significant driver of a professor's salary is their academic rank, which is tied directly to experience and scholarly achievement. The academic career path has a clear, hierarchical structure.

| Academic Rank/Experience Level | Typical Years of Experience | Average Salary Range (Source: Combined data from Salary.com & AAUP Reports) | Description |

| :--- | :--- | :--- | :--- |

| Lecturer / Instructor (Non-Tenure Track) | 0 - 5+ years | $50,000 - $75,000 | Primarily focused on teaching. Contracts are often short-term (1-3 years) and renewable. Less job security than tenure-track. |

| Assistant Professor (Entry-Level, Tenure-Track) | 0 - 6 years | $70,000 - $90,000 | The starting point for a PhD graduate on the tenure track. A probationary period of 5-7 years to build a record of teaching and research. |

| Associate Professor (Mid-Career, Tenured) | 7 - 12 years | $85,000 - $115,000 | Achieved tenure, granting job security. Expected to be an established scholar and a leader in teaching and service. |

| Full Professor (Senior-Level, Tenured) | 12+ years | $110,000 - $180,000+ | The highest academic rank. Reserved for scholars with significant, influential publications and a national/international reputation. |

| Adjunct Professor (Part-Time) | Varies | $3,000 - $6,000 per course | Paid on a per-course basis with no benefits or job security. This is a precarious but common form of academic employment. |

*Note: These salary ranges are estimates and can vary dramatically by institution type and location.*

### Beyond the Base Salary: Total Compensation

A professor's compensation package is more than just their 9-month academic salary. Understanding the full picture is crucial.

- Benefits: This is a significant part of the package. Universities typically offer excellent benefits, including:

- Health Insurance: Comprehensive medical, dental, and vision plans.

- Retirement Plans: Generous contributions to 403(b) or 401(a) plans, often through TIAA, with university matching that can exceed 10% of salary.

- Tuition Remission: Free or heavily discounted tuition at the university for the professor, their spouse, and their children. This benefit alone can be worth tens of thousands of dollars per year.

- Summer Salary: The standard academic contract is for nine months. Professors can supplement their income by teaching summer courses or, more commonly, by securing external or internal grants that pay a summer salary (typically up to two-ninths of their academic year salary) to support their research.

- Research and Travel Funds: Departments often provide an annual allowance for faculty to purchase books, attend academic conferences, and conduct research trips.

- Sabbatical Leave: After achieving tenure, professors are typically eligible for a paid sabbatical every seven years. This is a semester or a full year off from teaching and service duties to focus exclusively on a major research project.

- Administrative Stipends: Professors who take on administrative roles like Department Chair, Director of Graduate Studies, or Dean receive a significant stipend on top of their base salary to compensate for the additional responsibilities. This can range from an extra $5,000 per year for a smaller role to a six-figure increase for a Deanship.

When evaluating a job offer, it's essential to look at this entire compensation package, as a lower base salary at an institution with phenomenal benefits and research support can be more valuable than a higher salary at an institution with a less generous package.

Key Factors That Influence a Professor History Salary

The national averages provide a useful starting point, but a professor's actual earnings are determined by a complex interplay of factors. Understanding these variables is key to predicting your potential income and navigating your career path effectively. This section provides an extensive breakdown of the most critical elements that shape a professor history salary.

### `

`1. Type and Prestige of the Institution

This is arguably the most powerful factor influencing salary. The resources, mission, and prestige of a university or college directly dictate its compensation structure. The American Association of University Professors (AAUP) classifies institutions, and their annual salary survey provides the most reliable data in this area.

- Doctoral Universities (R1 - Highest Research Activity): These are the major research institutions, both public (e.g., University of Michigan, UC Berkeley) and private (e.g., Harvard, Stanford, Duke). They have the largest endowments and receive the most federal research funding. Consequently, they offer the highest salaries to attract and retain world-class scholars. A Full Professor of History at a top-tier R1 university can easily earn $180,000 to $250,000 or more. The pressure to publish and secure grants is immense.

- Doctoral/Professional Universities (R2, D/PU): This category includes many large state universities and some private institutions that grant doctorates but have a lower research profile than R1s. Salaries are very competitive but a step below the top tier. An Associate Professor here might earn in the $90,000 - $120,000 range. The balance is often more evenly split between teaching and research.

- Master's Colleges and Universities (Comprehensive): These institutions offer a full range of undergraduate programs and some master's degrees, but few to no doctoral programs. The primary focus shifts more towards teaching. Salaries are solid but generally lower than at doctoral universities. A Full Professor might earn between $95,000 and $130,000.

- Baccalaureate Colleges (Liberal Arts): These colleges, like Amherst, Williams, or Swarthmore, are known for their exclusive focus on undergraduate education, small class sizes, and close student-faculty interaction. While they prioritize teaching, they also expect high-quality scholarship. Salaries at elite, well-endowed liberal arts colleges can be surprisingly high, sometimes rivaling those at R1 universities. However, salaries at less wealthy liberal arts colleges will be more modest, often in the $80,000 - $110,000 range for senior faculty.

- Community Colleges (Associate's Colleges): These two-year institutions focus exclusively on teaching and workforce development. The minimum educational requirement is typically a Master's degree in History, not a PhD. Job security is often strong (with union representation), but salaries are the lowest among full-time positions in higher education. A full-time instructor with a PhD might expect to earn between $60,000 and $95,000, depending on location and seniority.

- Public vs. Private Institutions: Generally, private, non-profit universities pay higher average salaries than public universities, largely because of bigger endowments and freedom from state budget constraints. According to AAUP data, the average salary for a Full Professor at a private-independent doctoral university was $227,672 in 2022-23, compared to $173,436 at a public one.

### `

`2. Academic Rank and Tenure Status

As detailed in the previous section, rank is a direct proxy for experience and accomplishment, and it correlates directly with pay. The jumps are significant:

- The promotion from Assistant to Associate Professor upon receiving tenure typically comes with a substantial pay raise, often 10-15%, in addition to regular cost-of-living increases. This is a reward for successfully navigating the rigorous 5-7 year probationary period.

- The promotion from Associate to Full Professor is the final and most significant step. This promotion recognizes a sustained record of outstanding scholarship, teaching, and service that has earned the individual a national or international reputation. This often comes with another major salary increase and places the professor in the highest earning bracket at their institution.

### `

`3. Geographic Location

Where you live and work plays a major role in your salary, though it's often intertwined with the type of institutions located in that area. High-cost-of-living states and metropolitan areas must offer higher salaries to be competitive.

According to BLS data for all Postsecondary Teachers, the top-paying states are:

1. California: ($111,940 annual mean wage)

2. New York: ($110,650)

3. Massachusetts: ($104,870)

4. New Jersey: ($104,180)

5. Washington: ($99,570)

Conversely, states with a lower cost of living and fewer major research universities tend to have lower average salaries. States like Mississippi, Arkansas, West Virginia, and South Dakota are consistently at the lower end of the pay scale.

However, it's crucial to consider the cost of living. A $95,000 salary in a Midwestern college town may provide a far higher quality of life than a $120,000 salary in the San Francisco Bay Area or New York City. Many academics strategically seek jobs in low-cost-of-living areas with strong state university systems (e.g., in the Big Ten) to maximize their discretionary income.

### `

`4. Area of Historical Specialization

Within a history department itself, there isn't typically a formal salary difference between a professor of medieval European history and a professor of modern Latin American history who are at the same rank. Universities strive for internal equity.

However, specialization has a powerful *indirect* effect on salary by influencing job market demand.

- High-Demand Fields: Departments must always be able to staff large survey courses that are part of the university's core curriculum. Therefore, there is a perennial need for historians specializing in U.S. History and Modern European History. These fields are the largest and most competitive.

- Growing Fields: Areas that are currently growing and align with university strategic initiatives can be in high demand. These include World History/Global History, Digital Humanities (historians who can use computational methods), and histories of historically underrepresented groups (e.g., African Diaspora History, Asian American History). A candidate with a sought-after specialization may be able to negotiate a slightly higher starting salary.

- Public History: A PhD with a specialization in Public History—the practice of doing history for and with the public in settings like museums, archives, and government agencies—has an alternative career path outside of traditional academia, which can strengthen their negotiating position.

### `

`5. Research Productivity and Scholarly Reputation

At research-intensive universities (R1s and top liberal arts colleges), your value—and thus your salary—is heavily tied to your scholarly reputation. This is a merit-based system where prestige is currency.

- Publishing: A historian who publishes a groundbreaking book with a top university press (e.g., Harvard, Yale, Princeton, Oxford) will see their career and salary prospects skyrocket.

- Grants and Fellowships: Winning prestigious, nationally competitive fellowships from organizations like the Guggenheim Foundation, the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH), or the American Council of Learned Societies (ACLS) is a major mark of distinction that can lead to salary increases and outside offers.

- Outside Offers: The primary way senior professors receive significant, above-average pay raises is by getting a competing job offer from another university. Their current institution is then faced with making a "counter-offer" to retain their star scholar, which often involves a substantial salary bump. This practice means that the most renowned and productive scholars are also the highest paid.

### `

`6. Administrative Roles

A reliable path to a higher salary within academia is to take on administrative responsibilities. These roles come with significant stipends or salary increases to compensate for the added workload and reduced time for research.

- Department Chair: Typically a three-year rotating position. Comes with a stipend (e.g., $10,000-$20,000 extra per year) and a reduced teaching load.

- Center or Program Director: Leading an interdisciplinary center (e.g., a Center for European Studies) also comes with a stipend.

- Dean or Provost: Moving up into upper-level university administration (Associate Dean, Dean, Provost) means leaving the faculty ranks for a full-time administrative job. These positions come with executive-level salaries that are often double or triple that of a Full Professor.

Job Outlook and Career Growth

While the salary potential for a history professor can be strong, it is absolutely critical for any aspiring academic to have a clear-eyed and realistic understanding of the job market and career prospects. The path is exceptionally competitive, and the landscape of higher education is undergoing significant changes.

The Statistical Outlook

The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics projects that employment for all Postsecondary Teachers will grow by 8 percent from 2022 to 2032, which is much faster than the average for all occupations. The BLS anticipates about 118,800 openings for postsecondary teachers each year, on average, over the decade.

However, this aggregate data is dangerously misleading for a field like history. Much of this projected growth is in high-demand, career-oriented fields like healthcare, business, and computer science. The academic job market in the humanities, including history, is a very different story.

The Reality of the Humanities Job Market

The American Historical Association (AHA) tracks the academic job market for historians with meticulous detail, and their data presents a sobering picture:

- Oversupply of PhDs: For decades, universities have produced far more history PhDs than there are available tenure-track positions. This creates a hyper-competitive "buyer's market" where a single job opening for a history professor can attract 200-400 applications.

- Decline in Tenure-Track Positions: Universities, facing budget pressures, have increasingly relied on non-tenure track faculty (lecturers, instructors) and part-time adjuncts to teach introductory courses. The number of full-time, tenure-track history jobs advertised annually has seen a significant long-term decline.

- The Rise of "Adjunctification": A large percentage of undergraduate history courses in the U.S. are now taught by adjunct professors. These are highly qualified scholars (often with PhDs) who are paid a low per-course wage with no benefits, no job security, and no institutional support for their research. This is a precarious existence and a critical, often-overlooked reality of the academic profession.

This does not mean it's impossible to get a job.