Table of Contents

- [What Does a Flight Engineer Do? The Guardian in the Cockpit](#what-does-a-flight-engineer-do)

- [Average Flight Engineer Salary: A Deep Dive into Earnings](#average-flight-engineer-salary-a-deep-dive)

- [Key Factors That Influence a Flight Engineer's Salary](#key-factors-that-influence-salary)

- [Job Outlook and Career Growth: The Evolution of a Profession](#job-outlook-and-career-growth)

- [How to Embark on Your Career Path](#how-to-get-started-in-this-career)

- [Conclusion: Is a Career as a Flight Engineer or its Modern Equivalent Right for You?](#conclusion)

For anyone captivated by the symphony of a jet engine and the intricate dance of hydraulics, avionics, and mechanics that lifts tons of metal into the sky, the role of the Flight Engineer represents the pinnacle of technical mastery in aviation. This is not just a job; it's a calling for those who need to know not just *that* an aircraft flies, but *how* and *why* it does so, down to the last circuit and valve. But beyond the passion, a crucial question arises: what is the salary of a flight engineer? This guide will provide an exhaustive answer, revealing that while the traditional role has evolved, the earning potential for those with flight engineer-level expertise remains robust and rewarding, with salaries for experienced professionals often soaring well into the six-figure range, frequently between $80,000 and $150,000+ annually.

Years ago, during a tour of a maintenance hangar, I watched a team of senior technicians troubleshoot a recurring hydraulic issue on a massive cargo plane. The lead technician, a man with decades of experience, moved with a quiet confidence, his knowledge of the aircraft's systems almost intuitive. He was, in spirit and expertise, the modern-day flight engineer—the ground-based guardian of the machine. He explained that a pilot flies the plane, but someone like him ensures the plane is *fit* to fly. That conversation solidified my understanding that this expertise, whether in the air or on the ground, is the bedrock of aviation safety and commands commensurate respect and compensation.

This comprehensive guide will serve as your pre-flight checklist for a career in this demanding and rewarding field. We will dissect the salary of a flight engineer, explore the factors that can increase your earnings, analyze the surprising job outlook for those with these skills, and lay out a clear flight plan for you to get started.

---

What Does a Flight Engineer Do? The Guardian in the Cockpit

The Flight Engineer (FE), sometimes called an Air Engineer, is historically the third member of the flight crew in the cockpit, alongside the pilot (Captain) and co-pilot (First Officer). Seated at a complex panel of dials, gauges, and switches, the FE is the aircraft's systems specialist—the onboard master technician responsible for the health and performance of the machine itself. While advances in automation and computerization have made this dedicated third seat obsolete on most modern passenger aircraft (like the Boeing 787 or Airbus A350), the role remains critical on certain older, larger, or specialized aircraft, particularly in cargo, military, and some charter operations.

The core mission of a Flight Engineer is to ensure all aircraft systems function correctly before, during, and after a flight, thereby freeing the pilots to focus on navigation and flying. Their responsibilities are vast and require an encyclopedic knowledge of the aircraft.

Core Responsibilities and Daily Tasks:

- Pre-Flight Inspection: This is far more than a simple walk-around. The FE conducts an exhaustive interior and exterior inspection, meticulously checking engines, hydraulic systems, electrical systems, fuel tanks, landing gear, and pneumatic controls against a detailed checklist.

- Systems Monitoring and Management: In the air, the FE is the primary operator of the systems panel. They monitor engine performance, fuel consumption, cabin pressurization, air conditioning, electrical load, and hydraulic pressure, making constant adjustments to optimize performance and ensure safety.

- Fuel Management: The FE calculates the precise fuel load needed for a flight, considering factors like aircraft weight, weather, and potential diversions. During flight, they manage the fuel distribution between tanks to maintain the aircraft's center of gravity and ensure a steady supply to the engines.

- Troubleshooting and Emergency Procedures: If a warning light illuminates or a system malfunctions, the FE is the first responder. They diagnose the problem, consult flight manuals, and execute emergency procedures. Their ability to quickly and calmly resolve in-flight technical issues is paramount to the safety of the crew and cargo.

- Post-Flight Debrief and Maintenance Logging: After landing, the FE logs the performance of the aircraft during the flight, noting any anomalies or issues. This log is a critical communication tool for the ground maintenance crew who will service the aircraft for its next journey.

### A Day in the Life: Flight Engineer on a Trans-Pacific Cargo Haul

Imagine you're an FE on a classic Boeing 747-200 freighter, flying from Anchorage to Hong Kong.

- T-minus 3 hours: You arrive at the operations center, long before the pilots. You review the aircraft's maintenance log, weather reports, and the flight plan. You begin calculating the fuel requirements—over 150,000 kilograms of jet fuel.

- T-minus 2 hours: You head to the aircraft. For the next 90 minutes, you are in your element. You perform the meticulous pre-flight walk-around, checking engine fan blades, tire pressures, and hydraulic lines. Inside, you power up the aircraft, running tests on the electrical, pneumatic, and fire-suppression systems from your dedicated engineer's panel.

- T-minus 30 minutes: The pilots have arrived and are programming the flight management computer. You brief them on the aircraft's status and the fuel load. You confirm every system is "in the green."

- Takeoff and Climb: As the four massive engines roar to life, your eyes scan the engine instruments—Exhaust Gas Temperature (EGT), oil pressure, vibration levels. You call out "power stable" and monitor everything as the behemoth climbs to its cruising altitude of 35,000 feet.

- Cruise: For the next 8 hours, you are the vigilant guardian. Every 30 minutes, you log engine performance data. You actively manage the fuel, transferring it from center wing tanks to the main wing tanks to keep the aircraft perfectly balanced. A "generator off" light flickers on. You calmly pull out the Quick Reference Handbook (QRH), diagnose a tripped circuit breaker, and follow the procedure to reset it, restoring full power and averting a potential issue.

- Descent and Landing: As the plane descends, you manage the cabin pressurization to equalize with the destination's ground-level pressure. You configure the aircraft's systems for landing, monitoring brake temperatures and hydraulic pressures.

- Post-Flight: After a smooth landing and taxi to the cargo bay, you run the shutdown checklist. You complete your flight log, detailing the generator issue and the flight's overall performance, then hand the aircraft over to the Hong Kong maintenance crew. Your job is done until the return flight.

This example illustrates the immense responsibility and technical acumen required. While this specific role is now a niche, the skills it embodies are more critical to aviation than ever and have been absorbed by highly skilled ground and air personnel.

---

Average Flight Engineer Salary: A Deep Dive into Earnings

Analyzing the salary of a Flight Engineer requires a nuanced approach. Due to the rarity of the traditional role, salary data is less abundant than for pilots or mechanics. However, by combining data for the classic FE role with its modern equivalents—the highly experienced Aircraft Maintenance Technician (AMT) and Aerospace Engineer—we can construct a comprehensive picture of earning potential for professionals with this elite level of systems expertise.

The core takeaway is that this career path is financially lucrative, rewarding the immense responsibility and technical knowledge it demands.

### National Averages and Salary Ranges

For the dedicated Flight Engineer role that still exists, compensation is high, reflecting the seniority and specialized skills required.

- Payscale.com reports an average base salary for a Flight Engineer of around $111,500 per year. The typical range falls between $63,000 for those with less experience to over $184,000 for senior FEs on high-value routes or with defense contractors.

- Salary.com places the median salary for a Flight Engineer II (a mid-career professional) at approximately $116,988 per year, with a common range spanning from $103,425 to $128,735.

- Glassdoor data corroborates this, with total pay estimates often reaching $135,000+ per year when including additional compensation.

It's crucial to understand that these figures often represent professionals working for major cargo carriers like FedEx and UPS, or for military and government contractors, which are the primary employers of FEs today.

### Salary by Experience Level: A Career Trajectory

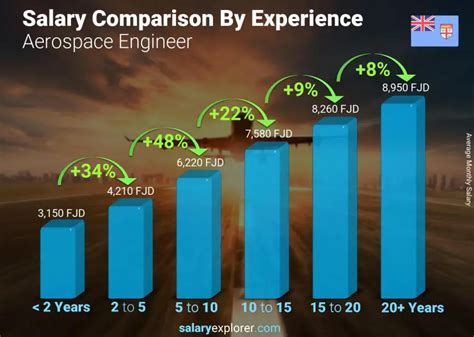

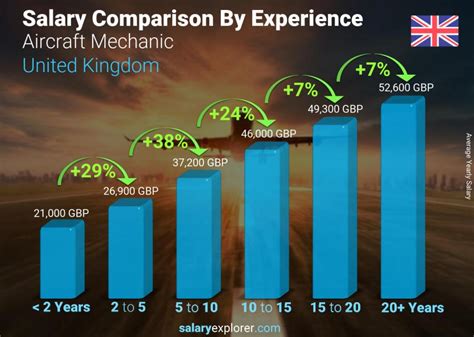

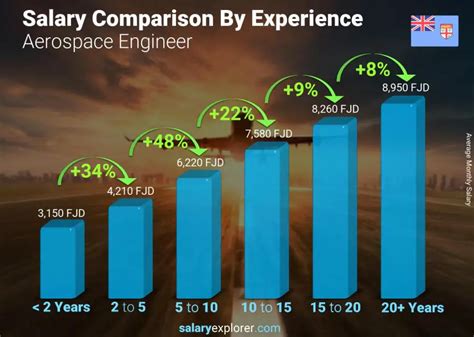

Compensation grows significantly with experience. The journey from a novice technician to a master FE or lead engineer is reflected in your paycheck. We will look at this through the lens of both a classic Flight Engineer and the more common path of a high-level Aircraft Maintenance Technician, as the experience progression is similar.

| Career Stage | Experience Level | Typical Annual Salary Range (Flight Engineer) | Typical Annual Salary Range (Lead Aircraft Technician/Inspector) | Notes |

| :--- | :--- | :--- | :--- | :--- |

| Entry-Level | 0-5 Years | $60,000 - $85,000 | $50,000 - $70,000 | Often starts as an A&P licensed mechanic or junior engineer gaining type ratings and experience on specific aircraft. |

| Mid-Career | 5-15 Years | $85,000 - $125,000 | $70,000 - $95,000 | Has significant experience on one or more complex aircraft types. May hold an Inspection Authorization (IA). |

| Senior/Lead | 15+ Years | $125,000 - $185,000+ | $95,000 - $130,000+ | A master of multiple aircraft systems. Often involved in training, safety oversight, or holds a check airman/check engineer status. |

*(Salary data is an aggregation and estimate based on Payscale, Salary.com, and industry knowledge. Technician salaries are informed by BLS and industry reports.)*

### Beyond the Base Salary: A Look at Total Compensation

The base salary is only one part of the financial equation. A career as a Flight Engineer or in a related high-level technical role comes with a robust benefits package that significantly increases total compensation.

- Overtime Pay: For technicians and engineers, especially in unionized environments at major airlines, overtime is plentiful and paid at 1.5x or 2x the base rate. This can add tens of thousands of dollars to an annual salary.

- Per Diem: For FEs who travel, a non-taxed daily allowance is provided to cover meals and incidental expenses while away from their home base. This can amount to a significant sum of tax-free income over a year.

- Bonuses and Profit Sharing: Many airlines and cargo carriers offer annual profit-sharing programs. When the company does well, employees receive a bonus, which can be equivalent to a month's salary or more. Sign-on bonuses are also common for in-demand, experienced technicians.

- License Premiums: An A&P (Airframe & Powerplant) license is the standard for technicians. Holding this license automatically adds a few dollars per hour to a mechanic's wage. Holding additional, more advanced certifications (like an FCC license for avionics or an Inspection Authorization) can add further pay premiums.

- Health and Retirement Benefits: Aviation companies typically offer excellent benefits packages, including comprehensive medical, dental, and vision insurance. Furthermore, 401(k) plans with generous company matching are standard.

- Flight Benefits: While more common for airline employees, one of the most cherished perks is access to free or heavily discounted flights for the employee and their family on the company's network and often on partner airlines.

When all these factors are combined, the total compensation package for a senior professional in this field can be substantially higher than the base salary figures suggest, making it a highly attractive long-term career.

---

Key Factors That Influence a Flight Engineer's Salary

A six-figure salary is not a given; it is earned through a combination of strategic choices in education, gaining deep experience, and positioning oneself in the right place, at the right company, with the right skills. Understanding these levers is the key to maximizing your earning potential throughout your career. This section will provide an exhaustive breakdown of the factors that determine your pay.

###

Level of Education and Certification

In aviation maintenance and engineering, certifications are often more impactful on salary than traditional academic degrees, though both play a vital role.

- The A&P License: For anyone working hands-on with aircraft in the U.S., the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) Airframe & Powerplant (A&P) license is the non-negotiable gateway. Obtaining this license from an FAA-approved Part 147 school is the first step. Simply holding this license instantly boosts earning potential. An unlicensed mechanic might earn $20-$25 per hour, while a newly licensed A&P mechanic at the same company could start at $30-$35 per hour.

- Inspection Authorization (IA): This is the next level up from an A&P. An IA allows a mechanic to perform annual inspections and sign off on major repairs and alterations. It requires holding an A&P for at least three years and passing a rigorous written exam. Holding an IA is a mark of a senior, trusted technician and directly translates to higher pay, often adding another $5-$10 per hour or leading to salaried inspector positions in the $90,000 - $115,000 range.

- FCC General Radiotelephone Operator License (GROL): For those specializing in avionics (the aircraft's electronic systems), this FCC license is often required. It demonstrates expertise in complex communication and navigation systems and opens the door to higher-paying avionics technician roles.

- Academic Degrees: While not strictly necessary for a technician or classic FE, a bachelor's or master's degree in Aerospace Engineering, Mechanical Engineering, or Aviation Maintenance Management can unlock different career paths. A technician with a bachelor's degree is a prime candidate for management and leadership roles (e.g., Maintenance Supervisor, Hangar Manager), which come with significantly higher salaries. For those on the Aerospace Engineer path, a B.S. is the minimum entry requirement, and a Master's or Ph.D. is typically required for specialized R&D or senior design roles, which are among the highest-paying in the industry.

###

Years of Experience

Experience is arguably the single most important factor in salary growth. Aviation places an immense premium on time-tested knowledge and troubleshooting ability. The salary trajectory is steep, especially in the first decade.

- Apprentice/Entry-Level (0-3 years): At this stage, you have your A&P license but limited hands-on experience. You'll likely work under the supervision of senior mechanics. Pay is hourly and typically in the $55,000 - $70,000 range annually, including some overtime. The focus is on learning and absorbing as much as possible.

- Journeyman/Mid-Career (4-10 years): You are now a trusted, independent technician. You've likely gained experience on one or two specific aircraft types (e.g., Boeing 737, Airbus A320). You're proficient in troubleshooting and routine maintenance. Salaries move into the $70,000 - $95,000 range. This is the stage where you might pursue an IA or specialize.

- Lead Technician/Senior FE (10-20 years): You are a master of your craft. You have experience on multiple aircraft, often wide-body jets (777, 747, A330). You are the go-to person for the most complex problems. You might be a Lead Technician, a Quality Control Inspector, or a classic Flight Engineer. Base salaries regularly exceed $100,000, and with overtime and premiums, total compensation can reach $120,000 - $150,000.

- Master Technician/Manager/Check Engineer (20+ years): At the pinnacle of your career, you may be managing a team, acting as a technical instructor, or serving as a check engineer who validates the skills of other FEs. In these roles, salaries can push towards $150,000 - $200,000+, especially at major cargo carriers or in executive maintenance management.

###

Geographic Location

Where you work has a massive impact on your salary. Compensation is highest in areas with a high concentration of aviation activity—major airline hubs, headquarters of aerospace manufacturers, and large military bases. However, these locations also typically have a higher cost of living.

High-Paying States and Metropolitan Areas:

- Washington: Home to Boeing's major manufacturing and assembly plants. Cities like Seattle, Everett, and Renton are epicenters of aerospace engineering and maintenance.

- California: A hub for both commercial aviation (Los Angeles, San Francisco) and cutting-edge aerospace R&D (Southern California's defense and space industry).

- Texas: Home to major hubs for American Airlines (Dallas-Fort Worth) and Southwest Airlines (Dallas), as well as significant defense and NASA operations in Houston.

- Georgia: Atlanta is the home of the world's busiest airport and the headquarters of Delta Air Lines, which operates a massive maintenance facility (Delta TechOps).

- Florida: A major hub for aviation, including commercial airlines in Miami and Orlando, and the heart of the space industry on the "Space Coast" around Cape Canaveral.

Salary Comparison by Location (for Aircraft Technician/Engineer roles):

| Location | Average Annual Salary (Approx.) | Why It's High/Low |

| :--- | :--- | :--- |

| San Francisco, CA | $105,000 | High concentration of airline operations, high cost of living. |

| Atlanta, GA | $92,000 | Major airline hub (Delta), large maintenance base. |

| Dallas, TX | $88,000 | Major airline hub (American), significant cargo operations. |

| Wichita, KS | $78,000 | "Air Capital of the World," but lower cost of living moderates salaries. |

| Rural Midwest | $65,000 | Fewer major employers, lower cost of living. |

*(Data is an illustrative aggregation from BLS and salary aggregators.)*

###

Company Type & Size

The type of company you work for is a major determinant of your pay scale and benefits.

- Major Passenger Airlines (e.g., Delta, United, American): These companies offer some of the highest pay scales in the industry, especially for experienced, unionized mechanics. They provide excellent benefits, including profit sharing and unparalleled flight perks. The work is fast-paced and focused on returning aircraft to service quickly and safely. Senior lead technicians can earn $120,000+ with overtime.

- Major Cargo Carriers (e.g., FedEx, UPS): Often considered the top of the pay scale for technicians and flight engineers. Because their business model depends entirely on aircraft reliability, they invest heavily in their maintenance and flight crews. It is not uncommon for senior technicians and FEs at these companies to earn $150,000 or more annually.

- Aerospace Manufacturers & Defense Contractors (e.g., Boeing, Lockheed Martin, Northrop Grumman): These companies employ a vast number of A&P mechanics and aerospace engineers. The work can range from building new aircraft to modifying and maintaining military fleets. Salaries are highly competitive, particularly for engineers and those with security clearances. An experienced aerospace engineer can expect to earn $130,000 - $180,000+.

- MROs (Maintenance, Repair, and Overhaul) Facilities: These are third-party shops that perform heavy maintenance for various airlines. Pay can be slightly lower than at major airlines, but they offer an incredible opportunity to gain experience on a wide variety of aircraft types, making them an excellent place to build a career.

- Regional Airlines: These smaller airlines typically operate smaller jets and have lower pay scales than the majors. A technician might start here to gain experience before moving to a major airline. Salaries are often 15-25% lower than their major airline counterparts.

###

Area of Specialization

Just as doctors specialize, so do top-tier aviation professionals. Developing deep expertise in a high-value area is a direct path to higher pay. This is the modern equivalent of the flight engineer's systems mastery.

- Avionics: This is one of the most lucrative specializations. Modern aircraft are more computer than machine. Technicians who can troubleshoot complex fly-by-wire systems, navigation equipment (GPS, INS), and communication arrays are in constant demand and command a significant pay premium.

- Wide-Body Aircraft: Technicians and engineers with experience and type ratings on large, complex aircraft like the Boeing 777, 747, or Airbus A380/A350 are paid more than those who only work on smaller, narrow-body jets. The systems are more complex and the financial stakes are higher.

- Powerplant (Engines): Specializing in a specific type of high-bypass turbofan engine (e.g., the GE90 or Rolls-Royce Trent series) can make you an invaluable asset. Engine work is highly specialized and critical to safety.

- Composite Repair: Modern aircraft like the Boeing 787 and Airbus A350 are built largely from carbon fiber composites. Repairing these materials requires special training and clean-room facilities. Technicians with these skills are at the forefront of aviation technology and are compensated accordingly.

- Non-Destructive Testing (NDT): NDT specialists use techniques like ultrasonic, eddy current, and X-ray to inspect aircraft structures for cracks and flaws without taking them apart. This requires advanced certification and is a high-paying, specialized technical role.

###

In-Demand Skills

Beyond formal certifications, a specific set of skills will make you a more effective and valuable professional, directly impacting your salary and career progression.

- Advanced Troubleshooting and Diagnostics: The ability to logically and efficiently diagnose a problem, from a faulty sensor to a complex hydraulic leak, is the most prized skill. This is learned through experience and a deep understanding of system schematics.

- Regulatory Knowledge: A thorough understanding of the Federal Aviation Regulations (FARs) is essential. Knowing what is legal, what needs to be documented, and how to do it correctly is critical.

- Systems Integration: Understanding not just how one system works, but how all the systems (hydraulics, electrics, pneumatics, avionics) interact with each other. This holistic view is the hallmark of a true senior professional or flight engineer.

- Soft Skills: These are often overlooked but are crucial for senior roles. They include:

- Calm Under Pressure: The ability to think clearly and act decisively during an in-flight emergency or a time-sensitive ground repair.

- Communication: Clearly explaining a technical problem to pilots, management, or other technicians.

- Teamwork and Leadership: Working effectively as part of a crew and, as you gain seniority, leading and mentoring junior technicians.

By strategically developing these factors, an aspiring flight engineer or aircraft technician can chart a course toward a career that is not only personally fulfilling but also financially exceptional.

---

Job Outlook and Career Growth: The Evolution of a Profession

The career outlook for a "Flight Engineer" is a tale of two realities. The traditional, in-cockpit role is a legacy profession with a declining forecast. However, the outlook for the professionals who embody the skills of a flight engineer—highly skilled aircraft mechanics, avionics technicians, and aerospace engineers—is stable and, in many areas, exceptionally strong.

### The Decline of the Classic Role, The Rise of the Modern Expert

As mentioned, automation and advanced flight deck design have systematically eliminated the need for a dedicated third crew member on new commercial aircraft. The functions of monitoring engines, fuel, and systems are now managed by sophisticated computer systems (like EICAS or ECAM) and overseen by the two pilots.