Introduction

Picture this: dawn breaks over the savanna, and you're in a Land Rover, preparing a tranquilizer dart for a collared lioness whose signal has been stationary for too long. Or perhaps you're in a sterile surgical suite, meticulously setting the tiny bones in the wing of an endangered California condor. This is the world of the wildlife veterinarian—a career that sits at the intersection of profound passion, rigorous science, and rugged adventure. It’s a calling for those who feel a deep connection to the natural world and possess the skill and determination to protect its most vulnerable inhabitants.

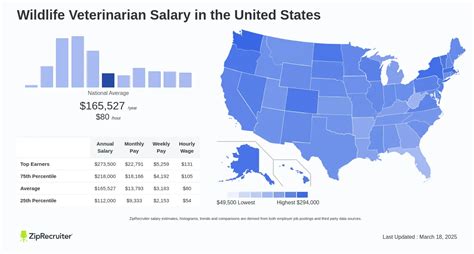

But passion, while essential, doesn't pay for student loans or put food on the table. For anyone considering this demanding yet incredibly rewarding path, a critical question arises: what does a wildlife vet salary actually look like? The answer is complex, nuanced, and far from the straightforward salary figures of a companion animal practitioner. While the overall median salary for veterinarians in the United States is robust, the niche field of wildlife medicine operates under a different set of financial realities. A wildlife vet's earnings can range from a modest non-profit salary of around $60,000 to over $180,000 for a top-tier, board-certified specialist at a major institution.

I once had the privilege of observing a team of wildlife veterinarians work to stabilize a rescued sea turtle, entangled and weak. The intense focus, the seamless collaboration, and the quiet, unwavering dedication in that room spoke volumes—it was a profound display of expertise driven by a purpose far greater than a paycheck. This guide is for those who feel that same pull. It aims to demystify the financial aspects of this career, providing a data-driven, comprehensive overview to help you align your passion with a sustainable and successful professional life.

### Table of Contents

- [What Does a Wildlife Veterinarian Do?](#what-does-a-wildlife-veterinarian-do)

- [Average Wildlife Vet Salary: A Deep Dive](#average-wildlife-vet-salary-a-deep-dive)

- [Key Factors That Influence a Wildlife Vet's Salary](#key-factors-that-influence-salary)

- [Job Outlook and Career Growth for Wildlife Vets](#job-outlook-and-career-growth)

- [How to Become a Wildlife Veterinarian: A Step-by-Step Guide](#how-to-get-started-in-this-career)

- [Conclusion: Is a Career as a Wildlife Vet Right for You?](#conclusion)

What Does a Wildlife Veterinarian Do?

The title "wildlife veterinarian" conjures images of heroic field interventions, but the reality of the job is far broader and more complex. These professionals are not just "animal doctors" for exotic species; they are multifaceted experts in medicine, conservation, public health, and research. Their work is critical for maintaining biodiversity, managing ecosystems, and preventing the spread of zoonotic diseases.

Unlike a small animal vet who treats individual pets, a wildlife vet's "patient" can be a single animal, an entire herd, a species, or even an entire ecosystem. Their responsibilities are incredibly diverse and vary significantly based on their employer and specialization.

Core Responsibilities and Daily Tasks:

- Clinical Medicine: This is the most familiar aspect of the job. It involves diagnosing illnesses, treating injuries, performing surgery, and prescribing medication for non-domestic animals. This can range from a routine dental cleaning on a red panda at a zoo to complex orthopedic surgery on a wild bald eagle at a rehabilitation center.

- Preventative Care & Population Health: A huge component of the job is proactive, not reactive. This includes developing and administering vaccination protocols, managing parasite control programs, and conducting routine health screenings for animal populations in zoos or in the wild. The goal is to prevent disease outbreaks before they start.

- Anesthesia and Immobilization: Safely anesthetizing wild animals, which can range from a 10-gram hummingbird to a 5-ton elephant, is a highly specialized and dangerous skill. Vets must be experts in pharmacology and remote drug delivery systems (dart guns).

- Conservation & Research: Many wildlife vets are at the forefront of conservation science. They may be involved in breeding programs for endangered species, collecting genetic samples, tracking disease prevalence in wild populations (like Chronic Wasting Disease in deer), or studying the health impacts of climate change and habitat loss.

- Necropsy and Pathology: When an animal dies, the wildlife vet’s job is often just beginning. Performing a necropsy (an animal autopsy) is crucial for determining the cause of death. This information can be vital for preventing other animals in a collection from succumbing to the same fate or for identifying a new disease threat in a wild population.

- Administration and Management: Senior vets often have significant administrative duties, including managing veterinary staff and budgets, ensuring compliance with state, federal, and international regulations (like the Animal Welfare Act and CITES), and writing grants to fund their work.

### A "Day in the Life" of a Zoo Veterinarian

To make this tangible, here’s what a typical day might look like for a staff veterinarian at a large, AZA-accredited zoo:

- 7:30 AM - 9:00 AM: Morning Rounds & Team Meeting. The vet meets with the veterinary technicians and keepers. They review overnight reports, discuss any animals showing signs of illness, and plan the day's procedures. Today, a silverback gorilla has a mild cough, and a wallaby isn't eating.

- 9:00 AM - 12:00 PM: Scheduled Procedure. Today's main event is a root canal on a snow leopard. This is a major undertaking involving a team of vets, techs, and a consulting veterinary dentist. The vet is responsible for calculating drug dosages, safely anesthetizing the 100-pound cat, monitoring its vital signs throughout the procedure, and overseeing its recovery.

- 12:00 PM - 1:00 PM: Lunch & Paperwork. Lunch is often eaten at the desk while catching up on detailed medical records. Every single observation, medication, and procedure must be meticulously documented.

- 1:00 PM - 3:00 PM: Field Calls within the Zoo. The vet drives the vet truck over to the gorilla exhibit to observe the coughing silverback, collecting a fecal sample for analysis. Afterwards, they check on the wallaby, performing a brief physical exam and deciding to administer subcutaneous fluids.

- 3:00 PM - 4:30 PM: Lab Work and Consultations. Back at the clinic, the vet analyzes bloodwork from a sick penguin, examines the gorilla's fecal sample under a microscope, and calls a colleague at another zoo to consult on a complex case involving a Komodo dragon.

- 4:30 PM - 5:30 PM: Meetings and Planning. The day ends with a meeting with the zoo's nutritionists and curators to discuss a new diet plan for the primate collection, followed by final checks on the recovering snow leopard before heading home—while remaining on call for any overnight emergencies.

This snapshot reveals a career that is intellectually stimulating, physically demanding, and emotionally resonant, requiring a unique blend of medical acumen, problem-solving skills, and deep-seated commitment.

Average Wildlife Vet Salary: A Deep Dive

Analyzing the salary of a wildlife veterinarian requires a nuanced approach. It is not a single, easily defined figure but a wide spectrum influenced by numerous factors. A critical first step is to understand the baseline for all veterinarians and then narrow the focus to the specific, and often less lucrative, world of wildlife medicine.

According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), the median annual wage for all veterinarians was $108,350 in May 2023. The lowest 10 percent earned less than $66,640, and the highest 10 percent earned more than $185,510. While this provides a helpful benchmark, it's important to recognize that this data is heavily weighted towards the nearly 80% of veterinarians working in private companion animal practice.

Wildlife veterinarians, particularly those in the early stages of their careers or working for non-profits, often fall into the lower end of this spectrum. The career is notoriously competitive, and the supply of passionate candidates often exceeds the number of available positions, which can suppress entry-level wages.

However, for those who persevere, complete advanced training, and secure positions at well-funded institutions, the earning potential can be substantial.

### Wildlife Vet Salary by Experience Level

Salary growth in this field is directly tied to the progression from post-graduate training to senior, leadership roles. The initial years are marked by low-paying but essential training positions, which are an investment in future earning potential.

Here is a typical salary progression, with data compiled and synthesized from sources like Salary.com, Payscale, and job postings from the American Association of Zoo Veterinarians (AAZV):

| Career Stage | Years of Experience | Typical Annual Salary Range | Key Characteristics |

| :--- | :--- | :--- | :--- |

| Veterinary Intern | 0-1 (Post-DVM) | $35,000 - $55,000 | A one-year, intensive, hands-on training program at a zoo, university, or large wildlife center. Pay is low, hours are long. This is a critical stepping stone. |

| Veterinary Resident | 1-4 (Post-Internship) | $45,000 - $65,000 | A highly competitive, three-year program focused on a specific discipline (e.g., zoological medicine). This is the primary pathway to becoming a board-certified specialist. |

| Entry-Level/Associate Vet| 0-4 (Post-Residency) | $70,000 - $95,000 | First official staff veterinarian role at a smaller zoo, aquarium, or rehabilitation center. May be the sole veterinarian on staff. |

| Mid-Career Veterinarian | 5-10 | $95,000 - $135,000 | A staff veterinarian at a larger institution or a department head at a smaller one. Often has more supervisory responsibilities and handles more complex cases. |

| Senior/Board-Certified Vet | 10+ | $120,000 - $180,000+ | A board-certified Diplomate of the American College of Zoological Medicine (ACZM). Typically holds a leadership role like Head Veterinarian or Director of Animal Health at a major zoo, university, or government agency. |

*Disclaimer: These figures are estimates and can vary significantly based on the factors discussed in the next section. For example, a senior vet at a small, non-profit rehab center may earn less than a mid-career vet at a large, well-funded metropolitan zoo.*

### Beyond the Base Salary: Understanding the Full Compensation Package

While base salary is the primary component of compensation, it’s crucial to evaluate the entire package, as benefits can add significant value, particularly in government and university roles.

- Base Salary: The fixed annual income, as detailed above. This is the largest part of a wildlife vet's compensation.

- Bonuses: Unlike in corporate or private practice settings, performance bonuses are very rare in the non-profit, academic, and government sectors where most wildlife vets work. Compensation is typically predictable and stable rather than incentive-based.

- Retirement Plans: This is a major differentiator. Government jobs (federal and state) often come with excellent pension plans and access to programs like the Thrift Savings Plan (TSP), a 401(k)-style plan with generous employer matching. Universities also typically offer strong 403(b) or 401(a) retirement plans. Non-profits may offer a 401(k) or 403(b), but employer contributions are often less generous.

- Health Insurance: Most full-time positions at reputable institutions will offer comprehensive health, dental, and vision insurance. The quality and cost of these plans can vary dramatically between employers. Federal government plans (FEHB) are generally considered top-tier.

- Paid Time Off (PTO): This includes vacation, sick leave, and holidays. Government and university positions often have more generous and clearly defined leave policies compared to smaller non-profits.

- Professional Development Funds: Many employers provide an annual allowance for continuing education (CE). This is critical for vets to maintain their licenses and stay current on the latest medical advancements. This may cover costs for attending conferences like the AAZV annual conference, which is also a vital networking opportunity.

- Student Loan Repayment Assistance: Given the high cost of veterinary school, programs like Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF) can be a massive financial benefit. Working full-time for a qualifying employer (like a 501(c)(3) non-profit zoo or a government agency) for 10 years can lead to the forgiveness of the remaining balance on federal student loans. This can be worth hundreds of thousands of dollars and is a major factor to consider when evaluating a lower-paying job at a qualifying institution.

When comparing job offers, it is essential to look beyond the base salary and calculate the total value of the compensation and benefits package. A $90,000 salary with excellent benefits and PSLF eligibility might be financially superior to a $100,000 salary with poor benefits and no loan forgiveness option.

Key Factors That Influence a Wildlife Vet's Salary

The wide salary ranges discussed above are driven by a confluence of interconnected factors. Understanding these variables is key to charting a career path that aligns with your financial goals. This is the most critical section for anyone trying to forecast their potential earnings in this specialized field.

###

Level of Education & Certification: The Board-Certification Premium

In wildlife medicine, your post-graduate training is arguably the single most important factor determining your career ceiling and earning potential.

- Doctor of Veterinary Medicine (DVM/VMD): This four-year degree is the non-negotiable entry ticket. The school you attend has less impact on salary than the specialized experience you gain *during* and *after* vet school. The average veterinary student graduates with over $190,000 in debt, a financial reality that looms large over early-career salary decisions.

- Internship (1 Year): As noted, this is a low-paying but essential first step. Completing a competitive internship at a respected zoo or academic institution is practically a prerequisite for being considered for a residency.

- Residency (3 Years): This is where true specialization occurs. A residency in Zoological Medicine, for instance, provides three years of intensive, mentored training in the medicine of non-domestic species. Completing a residency is the primary pathway to becoming board-certified.

- Board Certification (The Gold Standard): The ultimate credential in this field is becoming a Diplomate of the American College of Zoological Medicine (ACZM). To achieve this, a veterinarian must complete specific training requirements (typically a residency), publish research, and pass a rigorous two-day examination. Being "board-certified" or an "ACZM Diplomate" signals the highest level of expertise. It unlocks access to the most prestigious and highest-paying jobs, such as Head Veterinarian at a major zoo or a tenured professorship at a university. The salary difference between a non-certified vet and an ACZM Diplomate at the same institution can be $30,000 to $50,000 or more per year.

###

Years of Experience: The Path from Trainee to Leader

Experience directly correlates with salary, but the growth is not linear. It follows the trajectory of training and increasing responsibility.

- 0-4 Years (The Training Funnel): This period encompasses the internship and residency. Pay is minimal; the real compensation is the unparalleled training and experience. The financial sacrifice during these four years is an investment in a much higher future earning potential.

- 5-10 Years (The Established Professional): After residency, a vet becomes an Associate Veterinarian. In these years, they build a reputation, hone their clinical skills, and may begin to take on supervisory roles, such as mentoring interns. Salary growth is steady as they prove their value to the institution. A vet with 7 years of experience and a solid track record is a highly valuable asset. According to Salary.com, a Zoo Veterinarian's salary can increase by 20-30% from entry-level to this mid-career stage.

- 10+ Years (The Expert & Leader): Veterinarians with over a decade of experience, especially those who are board-certified, move into senior and leadership positions. They become Head Veterinarians, Directors of Animal Health, or Vice Presidents of Animal Care. In these roles, their responsibilities shift from purely clinical work to include strategic planning, budget management, staff leadership, and acting as the public face of the institution's veterinary program. These leadership roles carry the highest salaries in the field, often exceeding $150,000 - $180,000 at major institutions.

###

Geographic Location: Cost of Living and Concentration of Jobs

Where you work has a significant impact on your salary, though it's often tied to the local cost of living. High-paying areas are typically those with a high concentration of major zoos, research universities, and federal agencies.

- High-Paying States/Regions:

- California: Home to world-renowned institutions like the San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance and the Aquarium of the Pacific, as well as UC Davis, a leading veterinary school. High salaries are necessary to offset the extremely high cost of living.

- The Northeast (e.g., New York, Massachusetts): Major metropolitan zoos (Bronx Zoo), aquariums (New England Aquarium), and top-tier universities drive competitive salaries.

- Florida: A hub for both zoological parks (Disney's Animal Kingdom, Zoo Miami) and wildlife conservation efforts, particularly in marine and avian medicine.

- Washington, D.C. Metro Area: The presence of the Smithsonian's National Zoo and numerous federal government agencies (USDA, USFWS, NIH) makes this a hotspot for well-compensated government and institutional positions.

- Lower-Paying States/Regions: States in the Midwest and Southeast (outside of Florida) may offer lower salaries, but this is often balanced by a significantly lower cost of living. A $90,000 salary in Omaha, Nebraska (home to the excellent Henry Doorly Zoo) can provide a higher quality of life than a $115,000 salary in San Diego.

It's crucial to analyze salary figures in the context of local living expenses using a cost-of-living calculator.

###

Employer Type: The Biggest Salary Differentiator

The type of organization you work for is perhaps the most significant determinant of your salary and benefits package.

- Large, AZA-Accredited Zoos & Aquariums: These are the premier employers in the clinical space. Institutions like the San Diego Zoo, Bronx Zoo (WCS), Shedd Aquarium, and the National Zoo have larger budgets and are able to offer the most competitive salaries and benefits to attract top, board-certified talent.

- Government Agencies (Federal & State):

- Federal: Working for the USDA (Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service), US Fish & Wildlife Service (USFWS), or the National Park Service offers salaries based on the General Schedule (GS) pay scale. This provides transparent, predictable salary progression. For example, a veterinarian with a DVM and a residency could enter at a GS-12 or GS-13 level, which in 2024 could range from approximately $82,000 to $128,000 depending on location and experience. Federal jobs are highly sought after for their unparalleled job security and excellent retirement and health benefits.

- State: State fish and game departments or state diagnostic labs also employ veterinarians. Salaries are often lower than federal positions but still typically come with solid government benefits packages.

- Academic Institutions: Universities with veterinary schools (e.g., Cornell, UC Davis, Colorado State) employ wildlife vets as faculty. These positions blend clinical work at the university's teaching hospital, research, and teaching vet students. Salaries can be very competitive, especially for tenured professors, and are often supplemented by robust university benefits. A DVM/PhD dual-degree holder can command a very high salary in academia.

- Non-Profit Conservation Organizations & Rehabilitation Centers: This is the most mission-driven sector, and also typically the lowest paying. Organizations like the World Wildlife Fund (WWF), Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS - which also runs the Bronx Zoo), and smaller, local wildlife rehabilitation centers rely heavily on grants and public donations. While the work is incredibly rewarding, salaries can be significantly lower than in other sectors. A starting vet at a small rehab center might make $60,000 - $75,000. However, these jobs qualify for Public Service Loan Forgiveness, a critical financial consideration.

###

Area of Specialization: Clinical vs. Research vs. Policy

Within the broad field of wildlife medicine, different specializations lead to different career paths and salary expectations.

- Clinical Zoo & Aquarium Medicine: This is the most common path. Salary is tied to the size and budget of the employing institution, as detailed above.

- Wildlife Conservation & Field Medicine: This involves working "in the field" with free-ranging populations. These positions are often with NGOs, government agencies, or universities. Salaries are highly variable and often dependent on grant funding. An early-career field vet might make less than a zoo vet, but a senior scientist leading a major international conservation program could earn a very high salary.

- Research & Academia: Vets who focus on research, often earning a PhD in addition to their DVM, work in university or government labs. They study topics like epidemiology, toxicology, or reproductive physiology. This path can lead to high and stable salaries, particularly for tenured faculty at major research universities.

- Wildlife Rehabilitation Medicine: This specialization focuses on caring for injured and orphaned native wildlife with the goal of release. It is one of the most hands-on and emotionally rewarding areas, but also one of the lowest paid, as most rehabilitation centers are small non-profits with limited budgets.