In an era where medicine is rapidly shifting from a one-size-fits-all approach to a deeply personalized one, a small but powerful group of medical detectives stands at the forefront: clinical geneticists. These highly specialized physicians delve into the very blueprint of life—our DNA—to diagnose, manage, and prevent inherited disorders. For those with a passion for complex problem-solving, a deep curiosity about human biology, and a desire to provide life-altering answers to patients, a career as a clinical geneticist is one of the most intellectually stimulating and emotionally rewarding paths in medicine.

But what about the practicalities? A career this demanding and specialized surely comes with significant financial compensation. The journey is long and arduous, requiring a medical degree followed by years of specialized residency and fellowship training. Understanding the financial landscape is a critical component of deciding whether to embark on this path. The average clinical geneticist salary reflects this extensive training, often placing them in the upper echelon of physician earners, with typical annual compensation ranging from $200,000 to well over $350,000 depending on a host of factors we will explore in detail.

I once had the privilege of shadowing a clinical geneticist during a consultation with a young couple whose child was facing a constellation of mysterious developmental delays. After months of uncertainty and a battery of inconclusive tests from other specialists, the geneticist calmly walked them through the results of an exome sequence, pointing to a single, newly discovered gene variant that explained everything. The wave of relief and understanding that washed over the parents' faces was profound; they finally had an answer, a community, and a path forward. That moment crystallized for me the immense value of this profession—it’s not just about data and labs; it's about delivering clarity and hope in the face of profound uncertainty.

This comprehensive guide will serve as your roadmap to understanding every facet of a clinical geneticist's career, with a laser focus on salary, long-term outlook, and the steps required to join this elite field.

### Table of Contents

- [What Does a Clinical Geneticist Do?](#what-does-a-clinical-geneticist-do)

- [Average Clinical Geneticist Salary: A Deep Dive](#average-clinical-geneticist-salary-a-deep-dive)

- [Key Factors That Influence Salary](#key-factors-that-influence-salary)

- [Job Outlook and Career Growth](#job-outlook-and-career-growth)

- [How to Get Started in This Career](#how-to-get-started-in-this-career)

- [Conclusion](#conclusion)

What Does a Clinical Geneticist Do?

A clinical geneticist is a medical doctor (MD or DO) who has completed specialized fellowship training in medical genetics and genomics. Their primary role is to act as a diagnostic expert for conditions with a known or suspected genetic cause. They are the ultimate medical detectives, piecing together clues from a patient's physical exam, personal medical history, and detailed family history to determine the most appropriate genetic tests.

It is crucial to distinguish a clinical geneticist from a genetic counselor. While they work closely together as part of a genetics team, their roles and training are distinct. Genetic counselors are healthcare professionals with master's degrees who provide risk assessment, education, and support to individuals and families. A clinical geneticist, as a physician, can legally establish a doctor-patient relationship, make a formal medical diagnosis, prescribe treatments, and manage the overall medical care for patients with genetic disorders.

The scope of their work is incredibly broad, touching nearly every field of medicine. They may see patients of all ages, from a fetus with abnormalities detected on an ultrasound to an adult with a family history of early-onset Alzheimer's disease.

Core Responsibilities and Daily Tasks:

- Patient Consultation and Evaluation: Conducting comprehensive evaluations, which include taking a detailed three-generation family history (pedigree), performing a physical examination looking for subtle clues (dysmorphic features), and reviewing extensive medical records.

- Diagnostic Testing: Selecting, ordering, and interpreting a wide array of complex genetic and genomic tests, ranging from single-gene tests and chromosome analyses to whole exome and whole genome sequencing (WES/WGS).

- Making a Diagnosis: Synthesizing all clinical and laboratory information to provide a specific diagnosis for a genetic condition, which can include rare and ultra-rare diseases.

- Management and Treatment: Developing and overseeing management plans for patients with genetic disorders. This can involve prescribing medications, recommending specific therapies (physical, occupational), making referrals to other specialists, and monitoring for potential complications. For certain metabolic disorders, they manage highly specific diets and treatments.

- Counseling and Communication: Explaining complex genetic information to patients and families in an understandable and compassionate manner. This includes discussing inheritance patterns, prognosis, and recurrence risks for future pregnancies.

- Collaboration: Working as part of a multidisciplinary team that may include genetic counselors, pediatricians, oncologists, neurologists, cardiologists, surgeons, and social workers.

- Research and Academia: Many clinical geneticists, particularly those in academic medical centers, are actively involved in research to discover new disease-causing genes, develop novel therapies, and publish their findings to advance the field. They also play a critical role in teaching medical students, residents, and fellows.

### A Day in the Life of a Clinical Geneticist

To make this tangible, let's imagine a typical day for Dr. Anya Sharma, a clinical geneticist at a large academic children's hospital.

- 8:00 AM - 9:30 AM: Genomics Case Conference. Dr. Sharma meets with other geneticists, genetic counselors, and lab directors to review the most complex genetic test results from the past week. Today's agenda includes a child with an undiagnosed neurodevelopmental disorder whose exome sequencing revealed a "variant of uncertain significance" (VUS). The team debates the existing scientific literature and databases to decide if this VUS is the likely cause of the child's condition.

- 9:30 AM - 12:00 PM: Outpatient Clinic. She sees three patients. The first is a newborn with multiple congenital anomalies referred from the NICU. The second is a 7-year-old with suspected Marfan syndrome, a connective tissue disorder. The third is a follow-up with a teenager with phenylketonuria (PKU), a metabolic disorder, to adjust his diet and medication. For each patient, she performs a detailed exam, explains her thought process, and works with a genetic counselor to coordinate testing and support.

- 12:00 PM - 1:00 PM: Lunch and Charting. Dr. Sharma catches up on writing detailed consultation notes and orders from the morning clinic. These notes are critical for communicating her findings and recommendations to the referring physicians.

- 1:00 PM - 2:00 PM: Inpatient Consultation. She receives a page from the pediatric cardiology team. They have a patient with a specific heart defect and want a genetics consult to rule out associated syndromes like DiGeorge syndrome. She goes to the patient's bedside to perform an exam and speak with the family.

- 2:00 PM - 4:00 PM: Research and Administrative Time. Dr. Sharma dedicates this block to her research on genetic causes of epilepsy. She analyzes sequencing data, writes a section of a grant proposal, and responds to emails from collaborators.

- 4:00 PM - 5:00 PM: Telegenetics Follow-Up. She conducts a virtual visit with a family who lives several hours away to discuss the normal results of a genetic test, providing them with reassurance and closing a long period of diagnostic uncertainty.

This schedule highlights the immense variety and intellectual rigor of the profession, blending deep scientific analysis with compassionate patient care.

Average Clinical Geneticist Salary: A Deep Dive

The extensive education and specialized skills required of a clinical geneticist command a substantial salary. While compensation can vary significantly based on the factors we'll discuss in the next section, we can establish a solid baseline using data from authoritative industry sources. It's important to note that clinical genetics is a smaller specialty, so data is often bundled with "Pediatrics - Subspecialty" or "Physicians - Other" categories, but medical compensation reports provide specific insights.

According to the 2023 Medscape Physician Compensation Report, which surveys thousands of physicians across the United States, medical geneticists earn an average annual salary of $244,000. This report also notes an average incentive bonus of $36,000, bringing potential total compensation closer to the $280,000 mark for many practitioners.

Salary aggregators, which collect self-reported data and job listings, often show a higher range, likely reflecting more experienced professionals and those in private or industry settings.

- Salary.com, as of late 2023, reports the average Medical Geneticist salary in the United States is $256,011, with a typical salary range falling between $234,443 and $280,111. This data often represents base salary and does not always include bonuses or other incentives.

- Payscale.com indicates a wider range, with a median base salary around $205,000, but shows total pay reaching as high as $350,000+ when accounting for bonuses and profit-sharing, particularly for those in private practice.

- Doximity's 2023 Physician Compensation Report, a highly regarded source based on data from over 190,000 US physicians, places Medical Genetics in the lower third of physician specialties by pay. However, it's critical to contextualize this. "Lower third" for physicians is still an exceptionally high income relative to the general workforce. The report also highlights that compensation for nearly all specialties has been rising.

### Salary Progression by Experience Level

A clinical geneticist's salary follows a predictable and steep upward trajectory as they move from training to independent practice and gain experience.

| Experience Level | Typical Annual Salary Range (Total Compensation) | Notes |

| :--- | :--- | :--- |

| Medical Genetics Fellow (In-Training) | $70,000 - $85,000 | This is a training salary, set by the institution (GME office). It is not representative of post-training earnings but is a livable wage during the final 2 years of specialization. |

| Early Career Attending (0-5 Years) | $190,000 - $260,000 | Upon completing fellowship and becoming board-certified, salary jumps dramatically. Initial positions are typically in academic centers or large hospital systems. |

| Mid-Career (6-15 Years) | $250,000 - $330,000 | With established expertise, increased efficiency (seeing more patients or generating more RVUs), and potential leadership roles (e.g., Clinic Director), compensation rises significantly. |

| Senior/Experienced (16+ Years) | $300,000 - $400,000+ | Senior geneticists may be division chiefs, department chairs, or hold lucrative positions in the private/biotech industry. Their reputation and productivity command top-tier salaries. |

*Sources: Data synthesized from Medscape, Salary.com, Payscale, and general knowledge of physician compensation structures.*

### Unpacking the Full Compensation Package

The headline salary figure is only part of the story. A clinical geneticist's total compensation is a package of multiple components:

- Base Salary: The guaranteed annual income. In academic settings, this is often tied to rank (Assistant, Associate, or Full Professor). In private practice, it might be a lower figure, with a greater emphasis on productivity.

- Productivity Bonuses: This is a major component of physician pay. It is often tied to Relative Value Units (RVUs), a measure used by Medicare to determine the value of physician services. Each patient visit, procedure, and test interpretation is assigned an RVU value. Physicians who generate more RVUs often receive substantial bonuses.

- On-Call Pay: Geneticists often take calls from the hospital for urgent inpatient consults, for which they receive additional stipends.

- Academic/Administrative Stipends: Those who take on roles like Fellowship Program Director or Division Chief receive an extra stipend for their leadership duties.

- Profit Sharing: In private practice settings, partners share in the profits of the business, which can significantly boost income.

- Sign-On Bonus: To attract talent, especially in underserved areas, hospitals and practices often offer a one-time sign-on bonus that can range from $10,000 to $50,000 or more.

- Benefits Package: This is a highly valuable, non-taxable part of compensation. A typical physician benefits package is worth tens of thousands of dollars and includes:

- Health, dental, and vision insurance for the physician and their family.

- Malpractice insurance coverage.

- Generous retirement contributions (e.g., 401(k) or 403(b) with a significant employer match or pension plan).

- Continuing Medical Education (CME) allowance (typically $2,000 - $5,000 per year) to cover conference travel and professional development.

- Allowance for professional licenses, board fees, and society memberships.

- Paid time off and sick leave.

When evaluating a job offer, it is essential to consider the entire compensation package, as a lower base salary with a robust bonus structure and excellent benefits can be more valuable than a higher base salary with minimal extras.

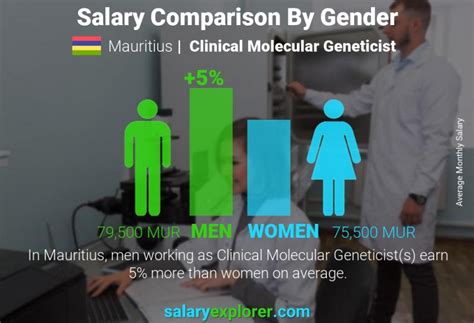

Key Factors That Influence Salary

While we have established a general salary range, the specific income a clinical geneticist earns is subject to a number of powerful variables. Understanding these factors is key to maximizing earning potential throughout one's career. This is the most granular and impactful part of understanding the real-world clinical geneticist salary.

### Level of Education and Certification

For a clinical geneticist, the educational floor is already incredibly high: an MD or DO degree. However, within this highly educated group, certain credentials can further enhance earning potential.

- Board Certification: Achieving board certification from the American Board of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ABMGG) is the single most important credential. It is a prerequisite for most reputable positions and signifies that the physician has met the highest standards of knowledge and practice in the specialty. Lacking board certification would severely limit job prospects and salary.

- Dual Board Certification: Many clinical geneticists first complete a residency in another specialty, such as Pediatrics or Internal Medicine, before their genetics fellowship. Being dual-boarded (e.g., in both Pediatrics and Medical Genetics) makes a candidate more versatile and valuable to a hospital or practice, which can translate into a higher salary. They can see general pediatric patients in addition to their genetics caseload, increasing their billing potential.

- Advanced Degrees (MD/PhD): A physician who also holds a PhD is known as a "physician-scientist." These individuals are highly sought after in academic medical centers for their ability to bridge clinical care with fundamental research. While their clinical salary might be comparable to an MD-only geneticist in the same institution, their overall compensation package is often larger. They can secure prestigious research grants (like those from the National Institutes of Health - NIH), which not only pay a portion of their salary but also elevate their status and the prestige of their institution, leading to higher academic rank and pay over time.

- Specialized Fellowships: While the standard is a 2-year Medical Genetics and Genomics fellowship, some individuals pursue an additional year of training in a sub-subspecialty, such as Medical Biochemical Genetics (metabolic diseases) or Molecular Genetic Pathology. This advanced expertise can lead to leadership roles in specialized clinics or laboratories, commanding higher salaries due to the unique skills required.

### Years of Experience

As detailed in the salary progression table, experience is a primary driver of income growth. This is not simply a reward for longevity but is directly tied to increased value.

- Fellow to Attending: The largest single pay increase in a physician's life is the transition from a fellow (trainee) to an attending (independent practitioner). The salary can easily triple or quadruple overnight, moving from a GME-funded stipend of ~$75,000 to an attending salary of $220,000+.

- The Early-Career Ramp-Up (Years 1-5): New attendings are learning to manage their own patient panels, becoming more efficient with charting, and building their clinical reputation. Their productivity (and thus their RVU generation) increases steadily during this time, leading to larger performance bonuses and strong annual salary increases.

- Mid-Career Mastery (Years 6-15): By this stage, a geneticist is a seasoned expert. They are highly efficient, can handle the most complex cases, and are often taking on mentorship and leadership roles. This is the period of peak earnings growth, where salaries can climb into the $250,000 - $330,000 range. They may transition from an academic role to a more lucrative private practice or industry position.

- Senior-Level Leadership (Years 16+): Senior geneticists leverage their reputation and experience. They may become Division Chiefs or Department Chairs, with salaries exceeding $350,000 or $400,000 due to the added administrative responsibilities. Others may become sought-after consultants for biotech and pharmaceutical companies or take on executive roles like Chief Medical Officer.

### Geographic Location

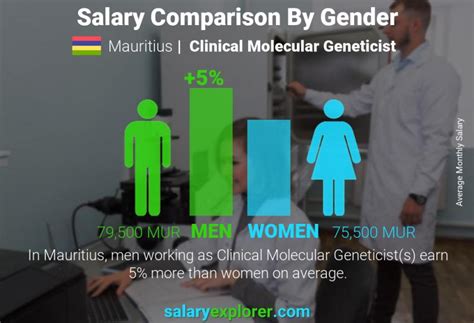

Where you practice medicine has a profound impact on your salary. This is driven by supply and demand, local market competition, and cost of living. Data from Doximity and Medscape consistently show significant regional variation in physician pay.

Highest-Paying States/Regions: Generally, states in the Southeast (e.g., Alabama, Georgia, Florida), Midwest (e.g., Indiana, Wisconsin), and some Western states (not including the coast) tend to offer higher physician salaries. This is often to attract doctors to areas with fewer large academic centers and a higher need for specialists. A clinical geneticist setting up a practice in a mid-sized city in one of these regions could command a significantly higher salary than one in a saturated coastal market.

Lower-Paying States/Regions: States in the Northeast (e.g., Massachusetts, Maryland, New York) and the West Coast (e.g., California) often have slightly lower average salaries for physicians. This is counterintuitive, as these areas have a high cost of living. The discrepancy is due to the high density of physicians, prestigious academic medical centers that can attract talent without offering top-tier pay, and dominant insurance payers that may have lower reimbursement rates.

City vs. Rural: Metropolitan areas with multiple academic centers (like Boston or San Francisco) may have more competition, suppressing salaries. Conversely, a geneticist willing to work in a less populated region or a smaller city may be the only specialist for hundreds of miles, giving them significant leverage to negotiate a higher salary and sign-on bonus from a local hospital system trying to build a genetics service.

Example Salary Variation by City (for a Medical Geneticist):

| City | Average Base Salary | Source |

| :--- | :--- | :--- |

| Charlotte, NC | ~$270,000 | Salary.com |

| Chicago, IL | ~$263,000 | Salary.com |

| New York, NY | ~$285,000 | Salary.com |

| San Francisco, CA | ~$300,000 | Salary.com |

*Note: Salary.com's city data often reflects higher cost-of-living adjustments but illustrates the significant variance. The true "take-home" value must be weighed against local taxes and expenses.*

### Company Type & Size (Practice Setting)

The type of organization a clinical geneticist works for is arguably the most significant factor influencing their salary and work-life balance.

- Academic Medical Centers: This is the most common setting for geneticists.

- Pros: Opportunities for teaching and research, intellectually stimulating environment, strong benefits (including pensions and tuition remission for family), and high prestige.

- Cons: Salaries are often lower than in private settings. Compensation is structured and less flexible, tied to academic rank. There is pressure to publish research and secure grant funding ("publish or perish"). A typical salary for an Assistant Professor might be $200,000 - $240,000, while a Full Professor and Division Chief could earn $300,000+.

- Private Practice (Group or Solo):

- Pros: Highest earning potential. Income is directly linked to the number of patients seen and the efficiency of the practice. Partners share in the business's profits. Greater autonomy over schedule and practice style.

- Cons: Requires significant business acumen. Responsible for overhead, billing, staffing, and marketing. Income can be less stable than a salaried position. A successful private practice geneticist could earn $350,000 - $500,000+.

- Large Hospital Systems (Non-Academic):

- Pros: Offer a blend of stability and strong compensation. Salaries are competitive and often come with robust productivity bonuses. Less pressure for research than in academia.

- Cons: Less autonomy than private practice. Work is often purely clinical, with fewer opportunities for teaching or research. Compensation might be in the $250,000 - $350,000 range.

- Industry (Biotech, Pharma, Diagnostic Labs):

- Pros: This is a rapidly growing and highly lucrative sector. Geneticists can work as Medical Directors or Clinical Science Liaisons for companies like GeneDx, Invitae, Pfizer, or Moderna. Salaries are very high, often with significant stock options and corporate bonuses.

- Cons: The work is non-clinical; you are not directly caring for patients. The roles are focused on lab test interpretation, strategy, and liaising with practicing physicians. This path can offer the highest compensation, with senior roles easily exceeding $400,000 - $500,000 in total compensation.

### Area of Specialization

While "Clinical Genetics" is the overarching specialty, many geneticists develop a niche focus area, often stemming from their primary residency training.

- Clinical Biochemical Genetics (Metabolic): These specialists manage patients with inborn errors of metabolism. This is a highly complex, lifelong management field that can be very demanding, often involving frequent on-call emergencies. This complexity and acuity can translate to higher compensation.

- Cancer Genetics: Geneticists who specialize in hereditary cancer syndromes (like BRCA-related cancer or Lynch syndrome) are in high demand in oncology centers. They work closely with oncologists and surgeons.

*